By Laury Grard

I. Context

A. Vapour chambers

There are many ways to humidify a document, and many conservators around the world have developed their own method. Water vapour chambers are a humidification technique I particularly like. The evaporation of water at room temperature produces individual water molecules in the gas phase (Levêque E. and Lelièvre C., 2023, p. 564–565). This is a very safe way to introduce moisture into a paper or parchment item in order to flatten it.

During my conservation training at the National Heritage Institute in Paris, a teacher showed us a very simple way to make mini chambers using an upside-down glass jar with damp blotter stuck to the bottom. This humidification technique is very practical and affordable, but it creates a circular treatment area, which is not always suitable.

Later, I discovered the micro solvent chambers with plaster (Van Velzen B., 2013). These are glass jars with lids into which a mixture of plaster of Paris (two parts plaster to one part water) has been poured to a quarter of the height. Once the plaster is dry, it can be impregnated with solvent. The jars are flipped upside-down to serve as small solvent vapour chambers. Plaster ensures good retention and diffusion of the solvent. There is also the advantage of avoiding the risk of the blotting paper falling onto the item. I tested this method with ethanol, isopropanol and acetone and used it successfully to remove pressure-sensitive tapes. However, when I tried it with water, the plaster retained it too well, and I couldn’t obtain sufficient relative humidity. I started thinking about how to improve and customise the mini humidification chamber while I was working on the mediaeval archives of the University of Paris.

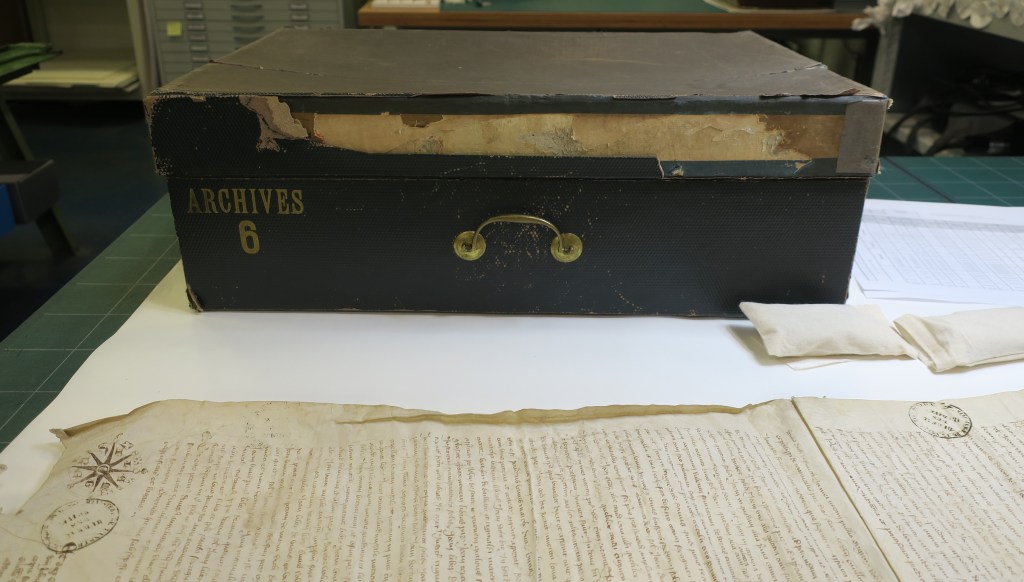

B. Digitisation project: the University of Paris’s archives

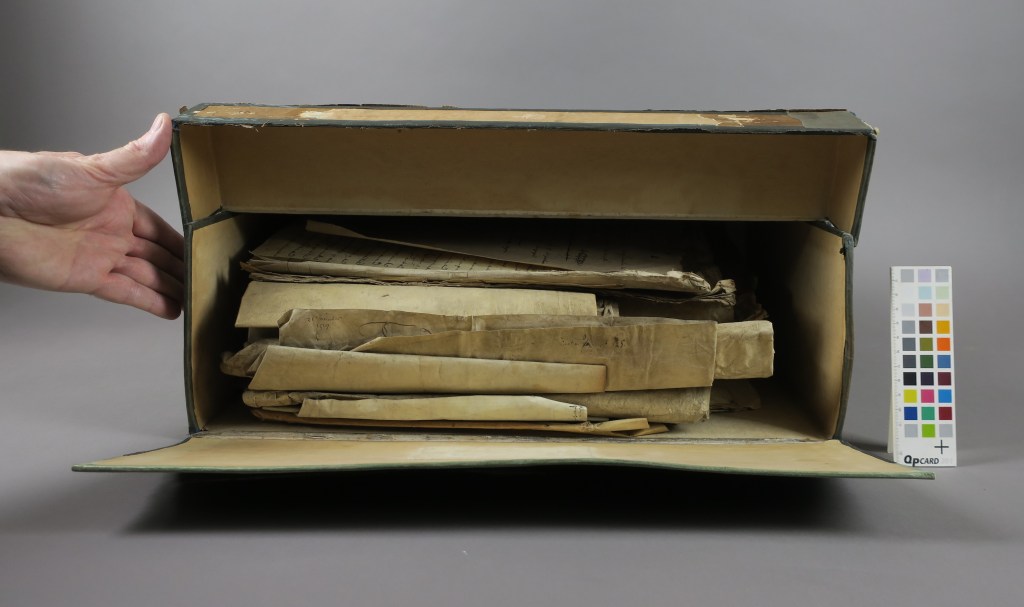

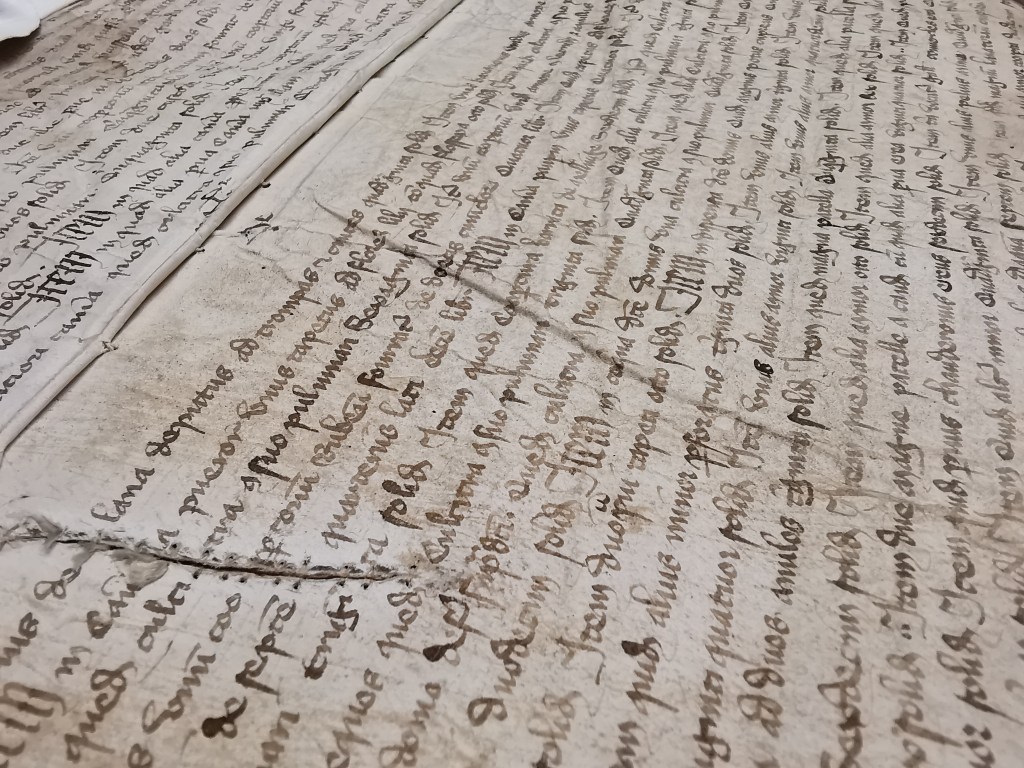

The archives of the University of Paris house a collection consisting of numerous administrative documents dating from 1213 to 1800, written on parchment and mostly sealed with wax. The collection includes deeds, regulations, correspondence, tax exemptions and all other documents pertaining to governing the University of Paris. Initially held by the National Archives of France, most of the collection was later moved to the Ministry of Public Instruction, before being returned to the University of Paris library in 1867. For decades, the single-leaf paper and parchment items have been stored in nineteenth-century archive boxes with no thought to keeping them flat.

A large digitisation project of this collection has been ongoing since 20201. Before the in-house digitisation, the items are surface-cleaned, flattened and consolidated in the conservation studio. I use our large cedarwood chamber for gentle overall humidification of objects with large distortions. However, many objects have only localised creases and therefore only need to be humidified in specific, limited areas. So I set out to find a solution to treat items locally, using a minimal intervention approach.

Because the vast majority of the documents are on parchment, there are some additional factors to consider before treatment. Parchment can undergo gelatinisation, a type of irreversible deterioration whose risk must be considered as soon as water is added (Lévêque E. and Leliève C., 2023, p. 561). It is essential to assess the condition of each parchment document individually before any wet treatment.

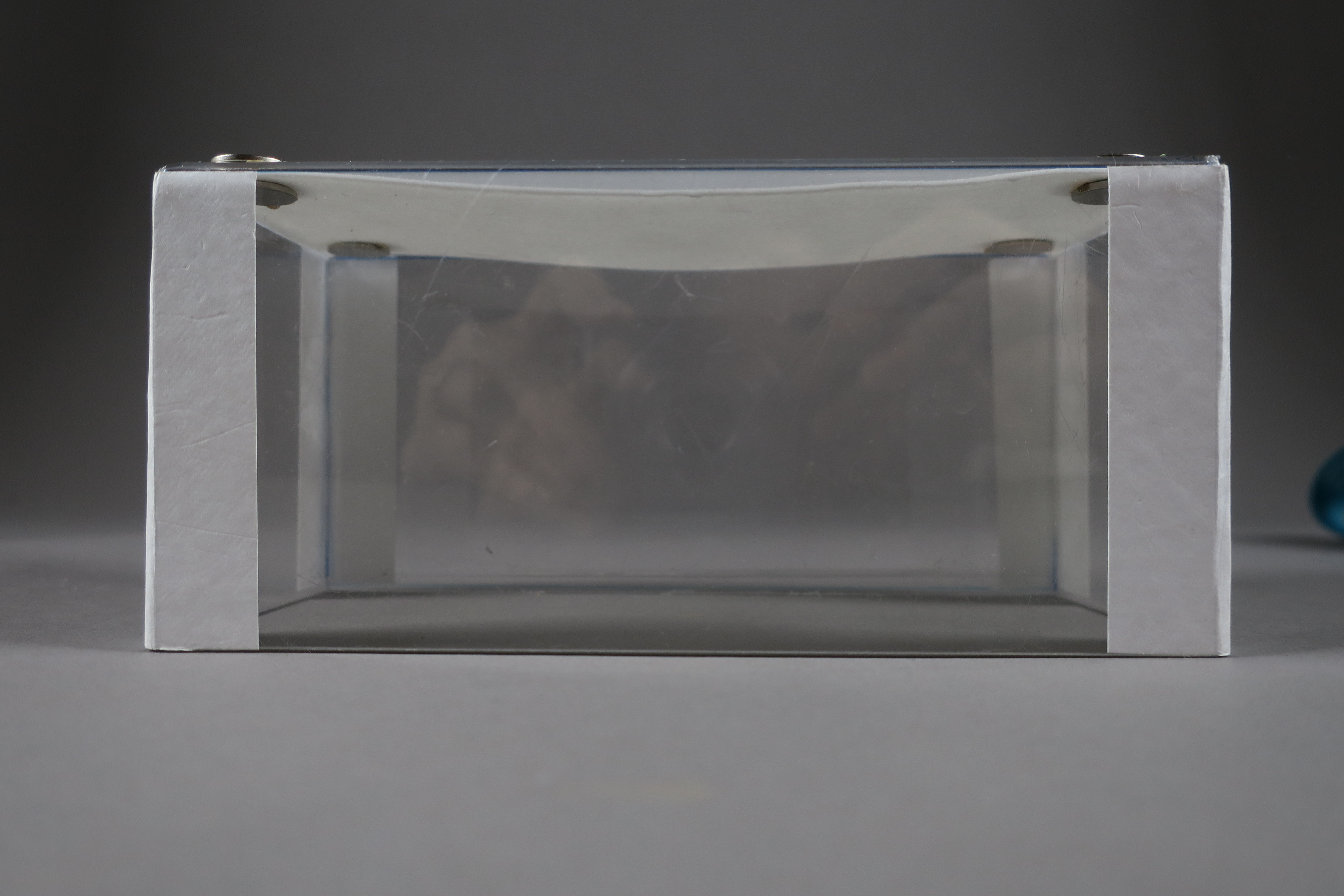

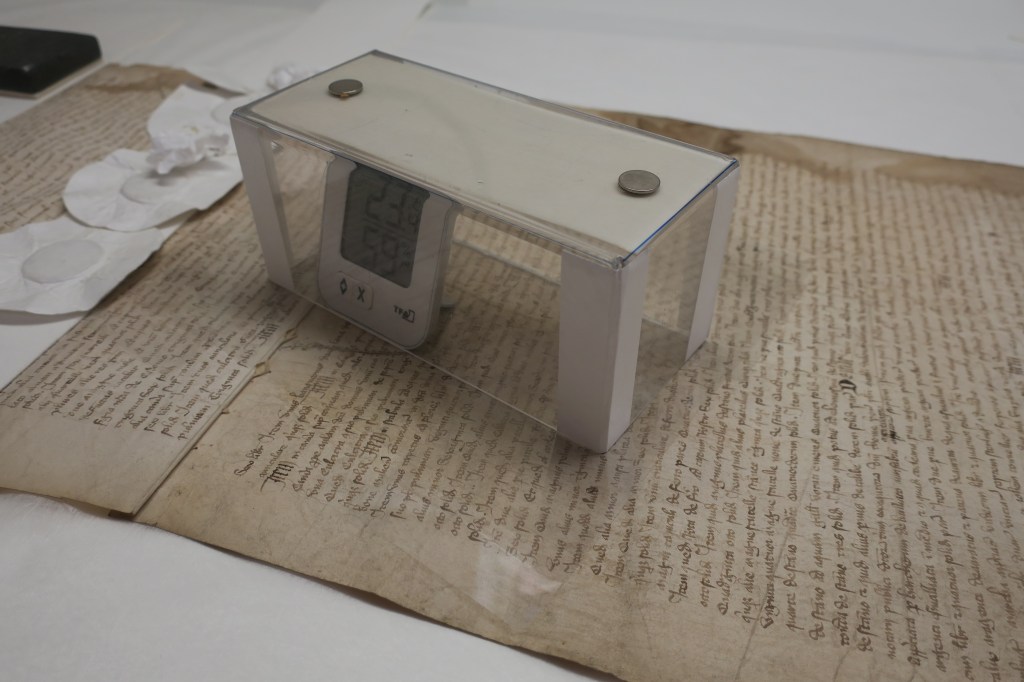

A bespoke mini transparent chamber equipped with a thermohygrometer to monitor the rise in humidity seemed like a good starting point. I also wanted a chamber that would be easy to use and reuse.

Book conservators at the Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de la Sorbonne (BIS) studio are used to working with PET-G (polyethylene terephthalate glycol-modified) plastic sheets to make exhibition book cradles2. It seemed reasonable to reuse the offcuts for the mini chambers. PET-G, better known under the trade name Vivak®, has the advantage of being easy to cut and fold with readily available equipment. It is also an Oddy-tested material (AIC, 2024), commonly used for temporary exhibition mounts over the last several years. Finally, it is transparent, which allows for visual control throughout the humidification treatment.

II. Step-by-step construction

1. The first step is to decide on your chamber’s dimensions. You can create either a bespoke chamber for a specific project or a set with a range of sizes. The height of the chamber is important: if the chamber is too tall, the item at the bottom will not receive enough humidity. You will also have to place your thermohygrometer inside, so its dimensions need to be considered as well. I generally make my chambers 8 cm tall.

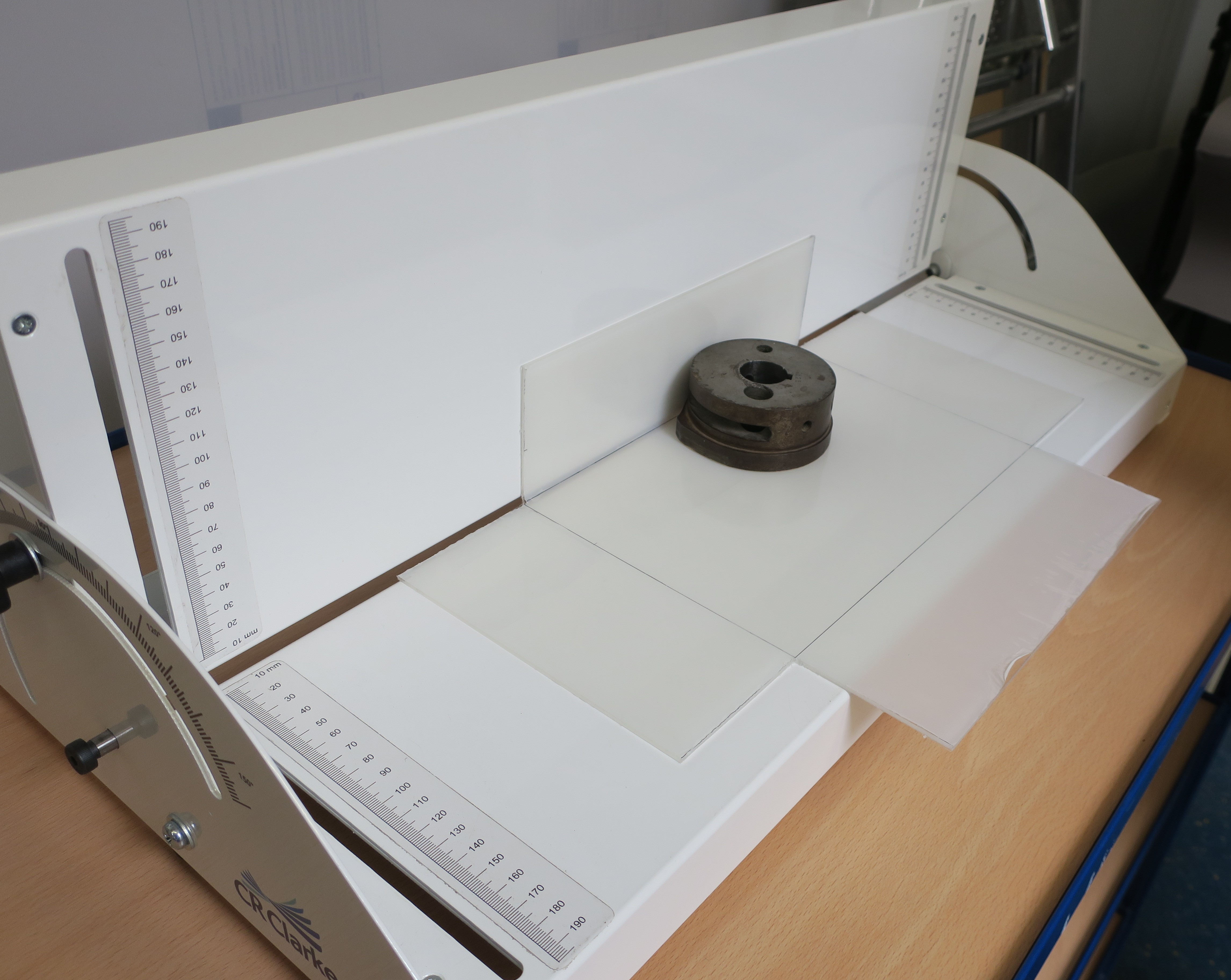

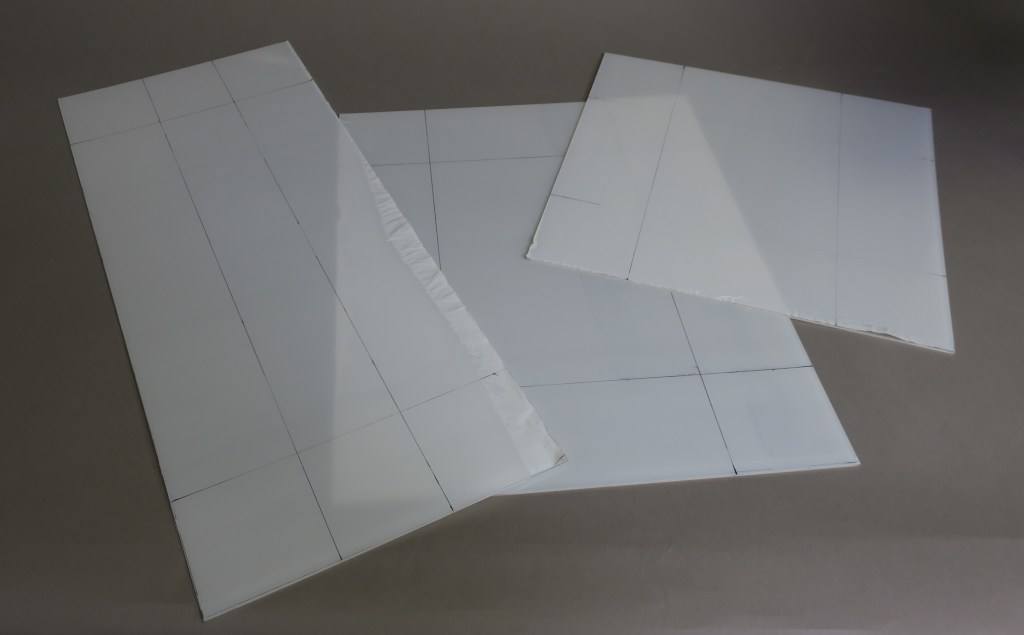

2. After tracing the dimensions onto the material with a marker, I cut the whole piece out with a board chopper. Then I cut out the four corners with a hacksaw.

3. Next, I sand the edges smooth with sandpaper.

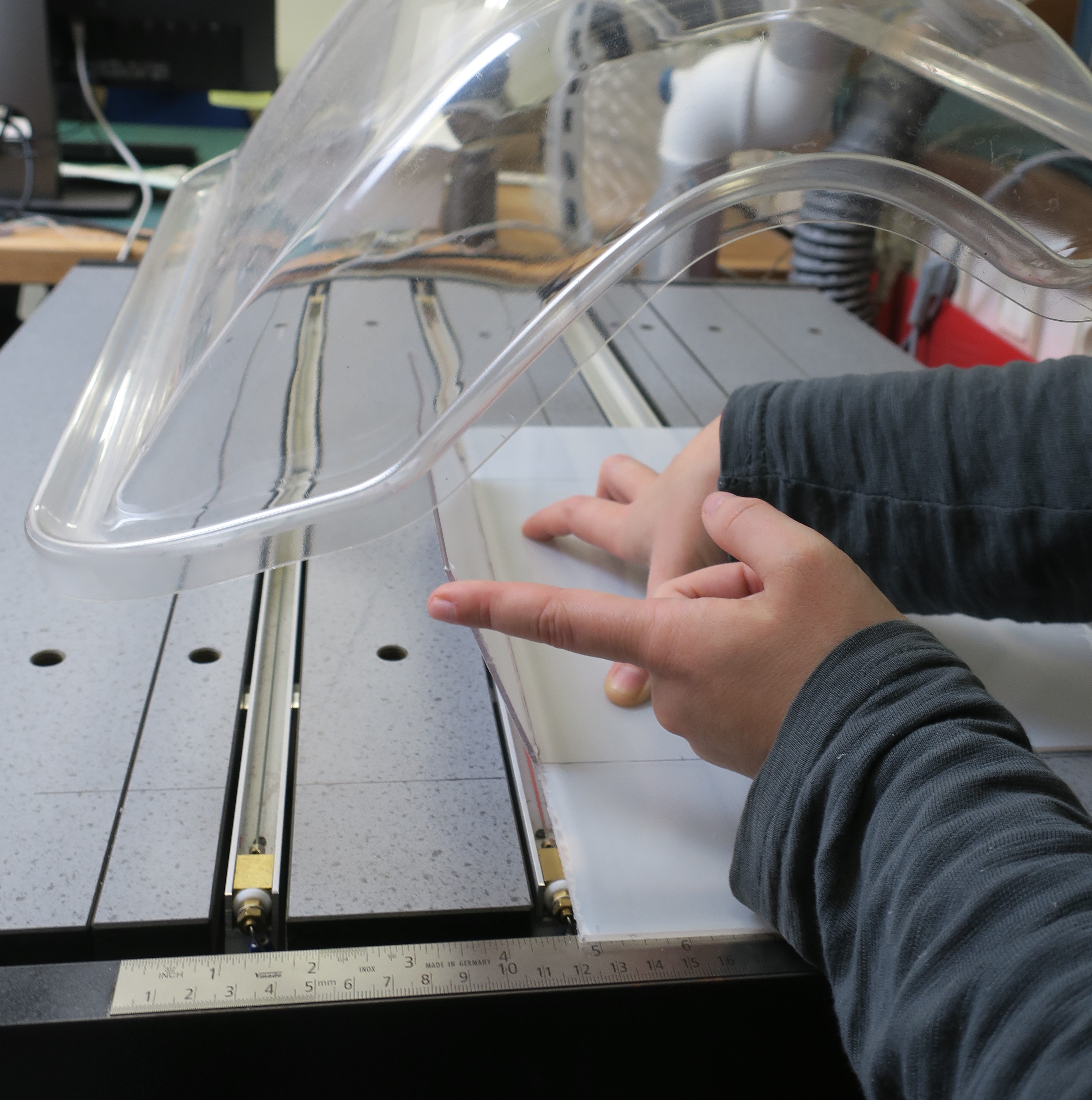

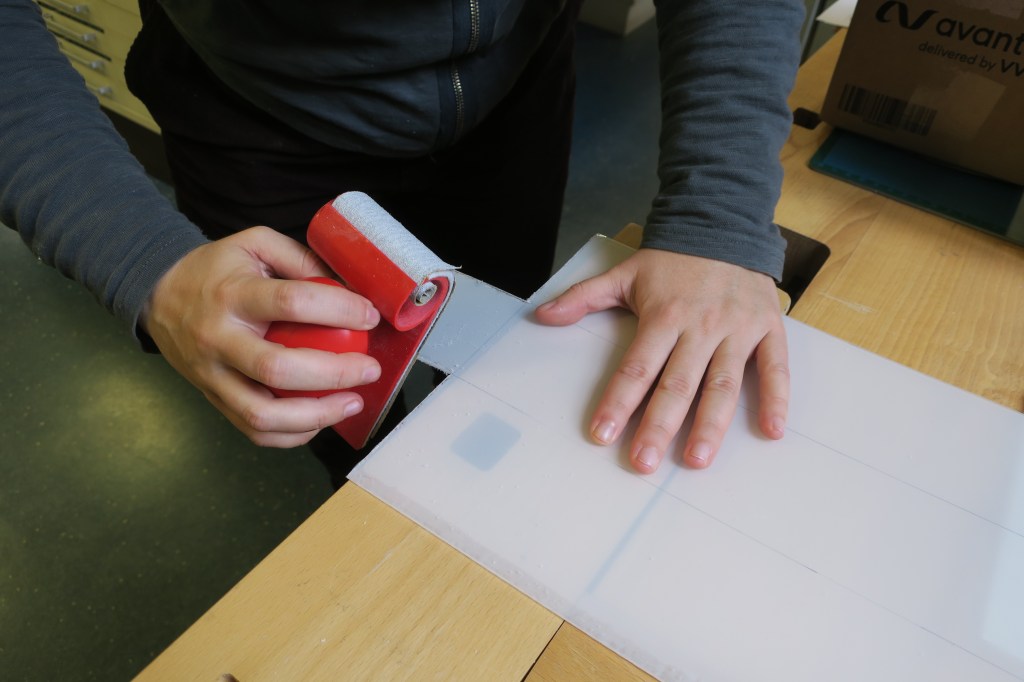

4. Now it’s time to fold it! PET-G can be bent by hand at room temperature, but this requires a certain amount of strength. It could save you the cost of a gym membership! Or you can take the easy way out and use a strip heater. In our studio we have a Shannon plastic-bending machine (model HRT 65). The use of the strip heater requires a fume extraction system.

Figs. 6 & 7 – Hot-bending the PET-G sheet, then bending the sides to 90°. ©BIS-DMLA/Laury Grard.

5. After the four sides are bent to 90°, the protective film can be removed from both sides of the PET-G sheet.

6. To improve the airtightness of the chamber, I put strips of Tyvek® adhesive tape at the corners.3

PET-G is a thermoformable material, which means that it can be reworked. The folds can be flattened out again using heat. We use this property to make our exhibitions eco-friendlier. The flattened PET-G sheets can be reused to make either new book cradles and lecterns or mini chambers.

III. Using the mini chamber

Setting up the mini humidification chamber is very simple. Simply cut a piece of blotting paper to fit into the bottom of the chamber. This blotting paper can be moistened by spraying or immersed directly in water.

The excess water must be blotted with another, dry blotter to avoid the risk of droplets forming when it is positioned in the chamber.

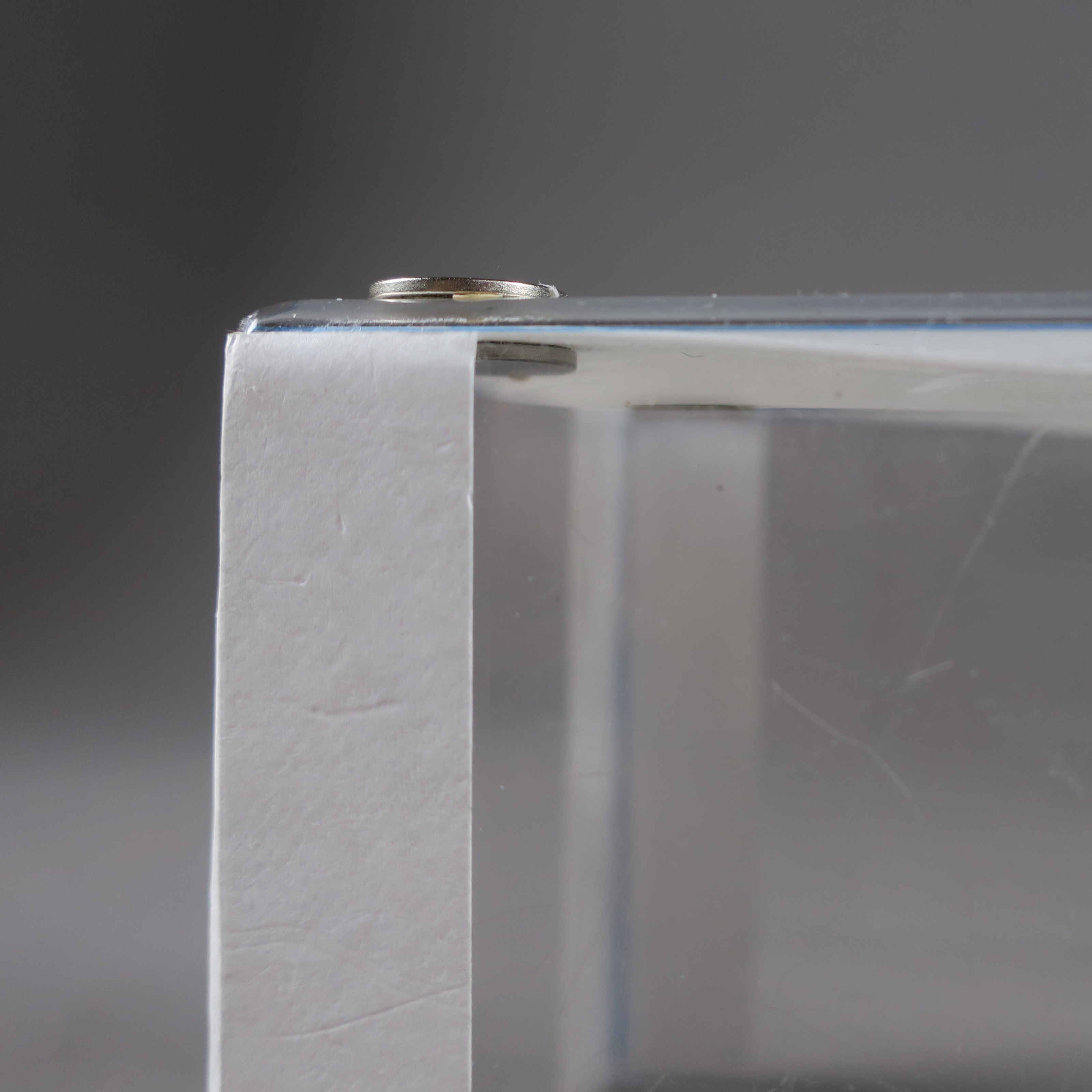

I use small magnets to hold the blotting paper inside the chamber.

Figs. 10 & 11 – Blotting paper held in place with magnets. ©BIS-DMLA/Laury Grard.

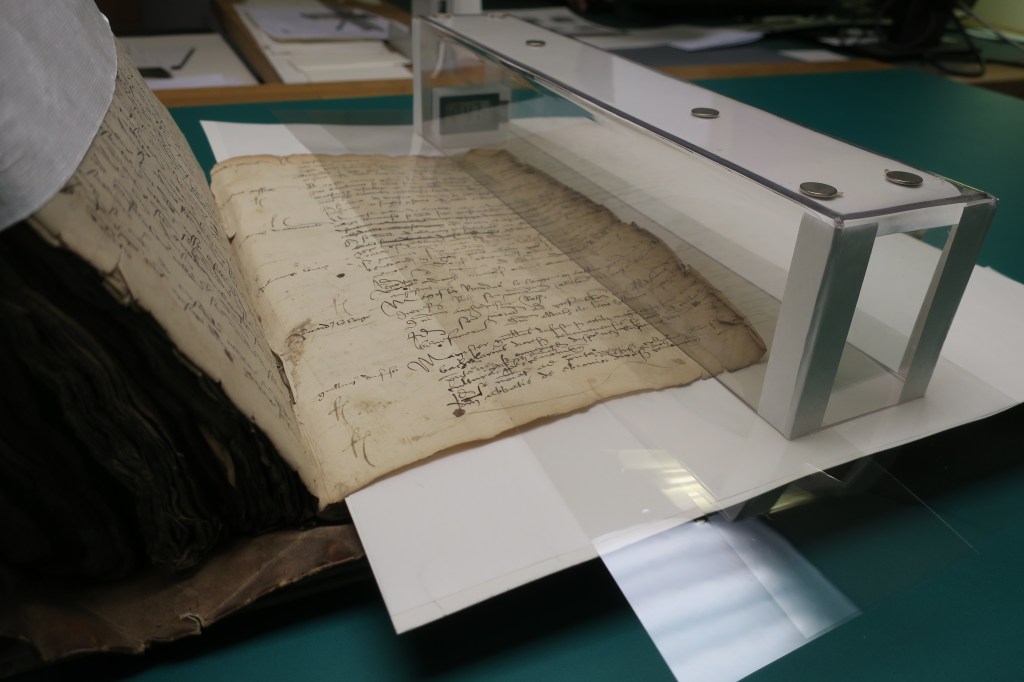

Since the treatment area is usually smaller than the chamber, I place pieces of polyester film around the area and then place the chamber on top with a thermohygrometer inside. You can place several chambers on the same item. Humidity rises more quickly than in a cedar humidification chamber, so don’t walk away from the item during the treatment.

IV. Pros and cons

One advantage of this humidification technique is that the moisture source is easy to install, rewet and replace. The blotting paper can also be impregnated with an alcohol/water mixture, often preferable for parchment items as it presents a lower risk for collagen than pure water (Lévêque, Lelièvre, 2023, p. 564). The chambers can be used for both flat items and bound books.

PET-G can be used to make customised chambers to suit your needs. For example, long, skinny chambers can be created to moisten only the margins of a book.

Several chambers can also be placed on the same item, so that different areas can be treated simultaneously.

However, there are also a number of potential drawbacks to bear in mind. Unlike cedarwood, PET-G does not allow any air exchange between the inside and outside of the humidification chamber. As a result, humidity can rise rapidly, and it is essential to stay close to the item and check the relative humidity level very regularly. On the other hand, parchment items require lengthy humidification, because the water molecules take a long time to reach the heart of the material and relax the collagen fibres (Lévêque E. and Lelièvre C., 2023, p. 560). Therefore, in some cases, a cedar chamber may be more effective than a PET-G mini chamber in achieving a lasting flattening. Finally, adding moisture in a localised manner can lead to tensions in the material between the moistened part and the adjacent dry parts. It is therefore not advisable to exceed 80% relative humidity inside the chamber. Although I’ve never experienced it, there is also some risk of condensation, particularly if the temperature in the room is not stable.

Conclusion

Mini humidity chambers have a number of advantages: they can be used to humidify tiny areas on both flat and bound items. PET-G is a convenient material for making mini chambers. It is easy to cut with a board chopper and can be bent either by hand or with a strip heater machine. Thermoformable and recyclable, this material can be reused several times.

Bibliography

AIC (2024). ‘Materials Testing Results – Case Construction Materials, MediaWiki’. Available at: https://www.conservation-wiki.com/wiki/Materials_Testing_Results_-_Case_Construction_Materials (Accessed: 01 February 2024).

Van Velzen B. (2013). ‘A Simple Solvent Chamber’ in Journal of Paper Conservation, IADA, vol. 14, issue 4, pp. 36–37.

Watkins S. (2002). ‘Practical Considerations for Humidifying and Flattening Paper’ in The Book and Paper Group Annual, vol. 21, pp. 61–76. Available at: https://www.culturalheritage.org/membership/groups-and-networks/book-and-paper-group/about-the-annual/bpgannual (Accessed: 01 February 2024).Lévêque E. and Lelièvre C. (2023). ‘Parchment Treatment’ in Bainbridge A., Conservation of Books. London: Routledge, pp. 560–572.

Footnotes

- The digitisation project at the archives of the University of Paris is part of a wider programme to highlight manuscripts, printed materials and iconographic sources relating to the history of the University of Paris held by the Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de la Sorbonne (BIS). This long-term programme began in early 2007. To date, 90 of 112 registers have been digitised. The digitisation of single-leaf items kept in boxes (a total of 1992 items, divided between 27 boxes) was started more recently (in 2020). To date, the contents of 7 boxes have been fully digitised. Items are available through the NuBIS digital library in the ‘Sources de l’histoire de l’université de Paris’ collection: https://nubis.univ-paris1.fr/page/item-sets ↩︎

- The BIS conservation studio sources PETG from the plastics manufacturer Richardson. ↩︎

- I use the Easy Bind® Tyvek® from the German supplier Neschen (ref.: 35044). ↩︎

Biography

Laury Grard holds a Diploma of Bookbinding and Gilding (a three-year program at the Lycée Professionnel Corvisart-Tolbiac, Paris) and an MA in book conservation (a five-year program at the Institut National du Patrimoine, Paris). She began her book conservation career with a six-month contract at the Victoria and Albert Museum, followed by a three-year position at the Paul Valéry Montpellier 3 University (SCDI, Montpellier). In early 2022, she joined the conservation team at the Sorbonne Interuniversity Library (Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de la Sorbonne or BIS, Paris). She divides her time between doing conservation treatments and conducting a research project on conservation bindings for mediaeval manuscripts on parchment. This project is a partnership with her colleagues at the BIS book conservation studio and the SCDI Montpellier book and paper conservation studio, as well as with the solid mechanics laboratory at the École Polytechnique of Paris. She is particularly interested in book mechanics.

An interesting read. What humidity level do you wish to get?

LikeLike

Thank you very much for your reading! In general, I aim for 80% relative humidity. Below that, it can be difficult to flatten the parchment or paper and above that there is a high risk of degradation of the parchment or inks (particularly in the case of iron gall inks).

LikeLike