By Clara Malinka

Background

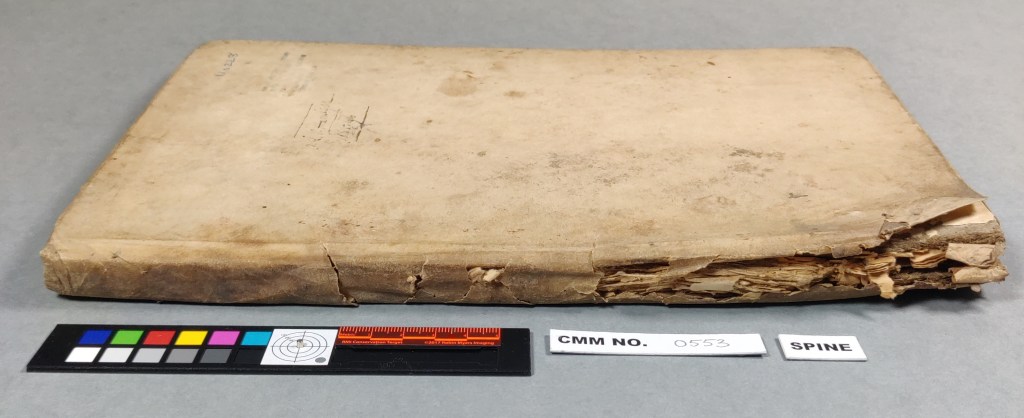

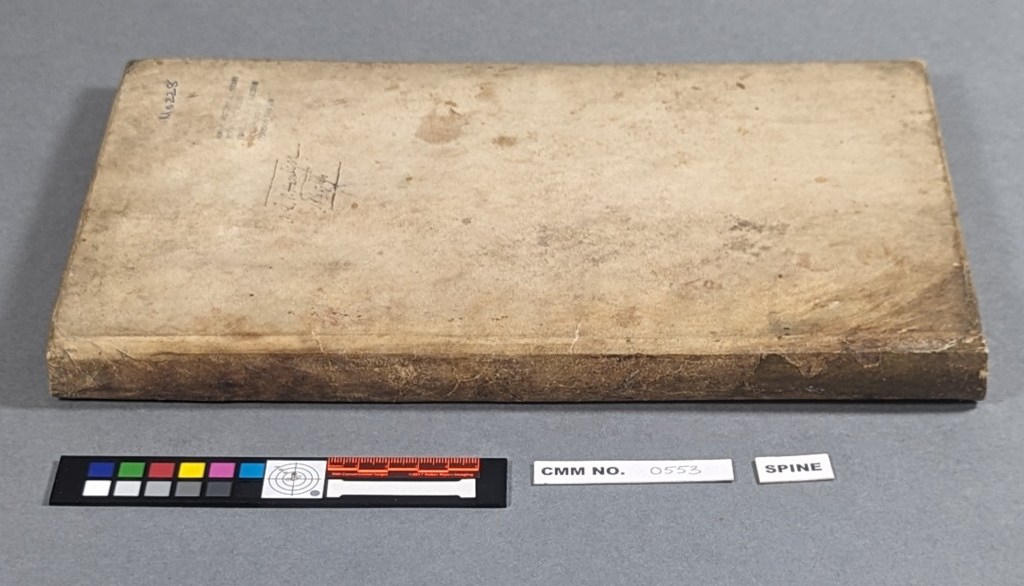

The Admiralty Library contains an extensive collection of naval books and records, including a handwritten parchment stationery case binding logbook kept by Osbert Hambyn, naval cadet and midshipman on the HMS Liverpool from 1865 to 1866 (Figure 1).

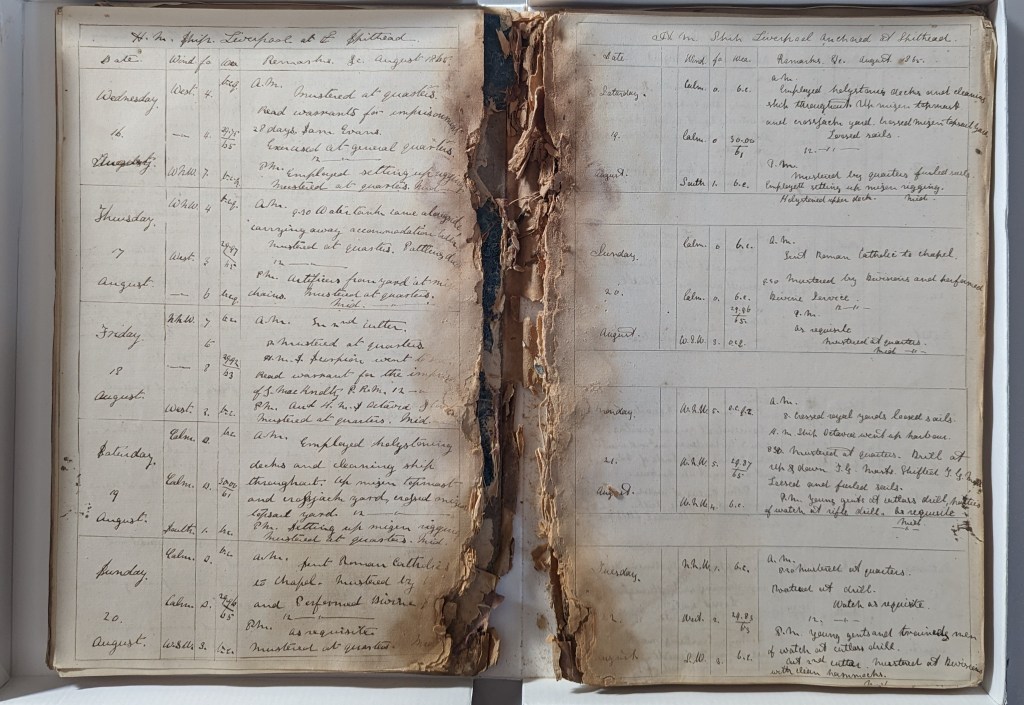

The binding presented with a plethora of conservation issues, but mainly extensive water and mould damage along the spine of the textblock, which caused the intermolecular chemical bonds in the paper to fall apart, giving the spine folds a felt-like appearance (Figure 2). It was important to retain original structural elements whilst ensuring functionality.

The flat parchment sewing supports were missing, along with most of the sewing, except for the few strands found in the centres of sections. It was clear that in order for this binding to be handleable, the sections had to be repaired and the textblock, resewn.

Treatment

Testing confirmed that the mould was not active. A fume hood and a vacuum cleaner with a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filter was used to facilitate dry cleaning to remove dry spores. Afterwards, a 1:4 water and isopropanol solution was used to disinfect the dry-cleaning brushes and surfaces that had been in contact with the book. The next treatment step was to consolidate the textblock. With the spine folds in such a poor state, understanding the collation of the sections was a challenge. Based on the few existing centres of the signatures, an apparent collation order emerged, and by observing which pages were paired, consolidation could begin using solvent-set remoistenable Japanese tissue.

The pages in the textblock were written with iron gall ink and did not show signs of active corrosion. Therefore, a phytate treatment was not chosen, as it was considered too invasive. Applications of moisture needed to be limited due to the presence of iron gall ink. Furthermore, due to the highly degraded textblock substrate, consolidation needed to be completed with remoistenable tissue, as application of adhesive directly to the felted substrate would have disrupted the paper fibres. Hence, a solvent-set tissue with 2% Klucel G reactivated with isopropanol was selected for repairs.

Infills were staggered (Figure 3) to prevent excess buildup in one place on the textblock. Thin 3.5 gsm Japanese tissue was used for these repairs to keep swell to a minimum, as it was important for the repaired textblock to fit back into its original case. The repairs were done on a suction table. As many of the leaves were not connected at the spine fold, the suction table was used to help realign and secure the fragmented leaves. This allowed for more control when applying the first layer of remoistenable tissue.

The suction table procedure was as follows.

- The fragmented leaves were aligned on a layer of Bondina; the suction was turned on, and a layer of remoistenable tissue placed over the leaves (Figure 4) and reactivated with solvent.

- The suction was then turned off; blotter used as a support to flip the now-connected leaf over onto another Bondina sheet, and the suction turned back on.

- Losses in the leaf were infilled, and the fills were adhered with 2% Klucel G in isopropanol to the exposed remoistenable tissue. Another layer of remoistenable tissue was staggered and reactivated with solvent.

How was the solvent-set tissue reactivated?

Multiple methods of solvent application were tested: direct application with a flat brush, an ultrasonic mister and blotter dampened with solvent and patted on the tissue. Of these methods, the solvent-dampened blotter was the best, as it successfully reactivated the adhesive in the tissue while minimising the use of solvent.

After each leaf was consolidated, the textblock was sewn in the original style with three parchment slips (Figure 5). Unbleached linen – adhered using 5% gelatin, 220 bloom – was used to replace the transverse cloth linings (Figure 6).

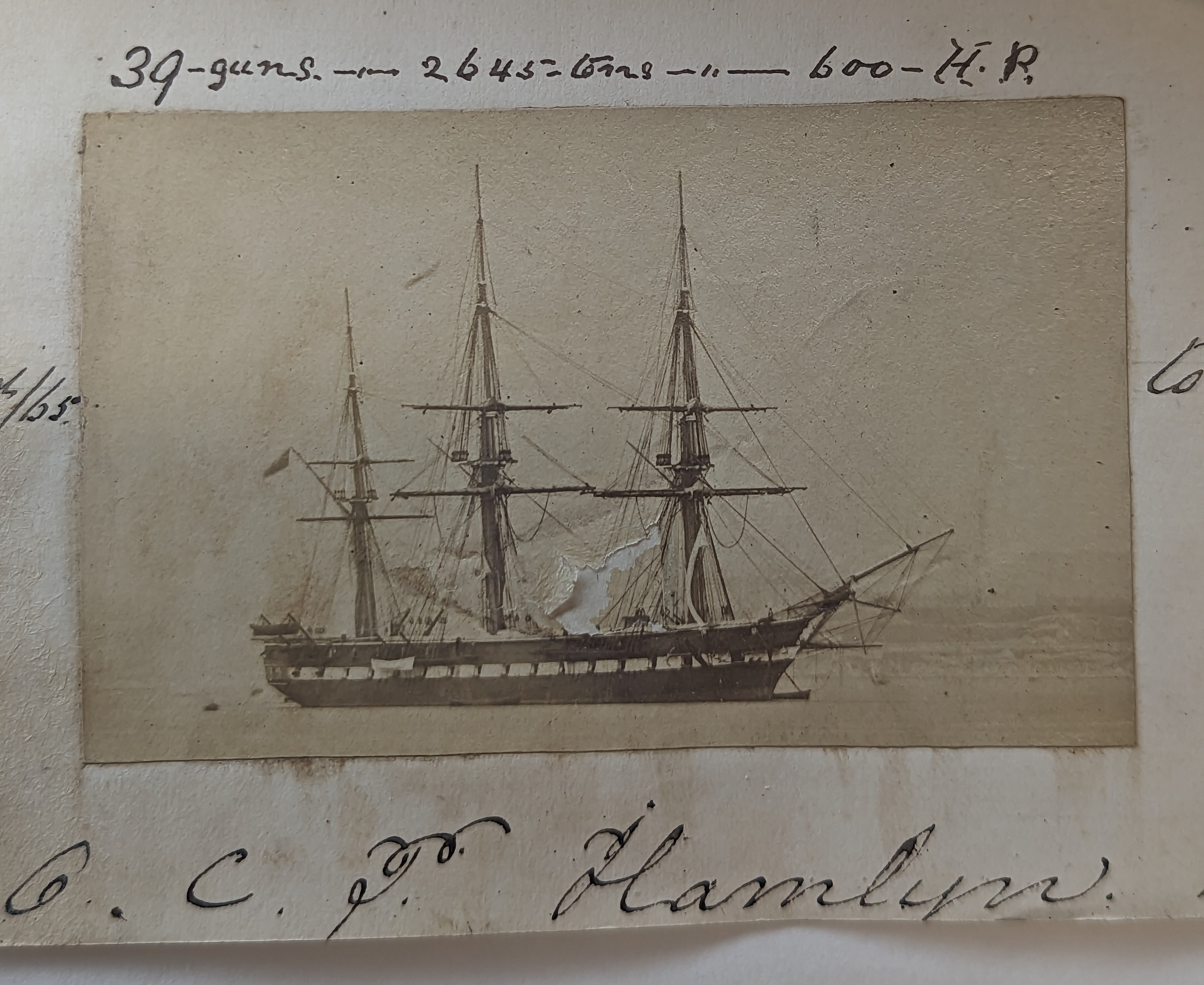

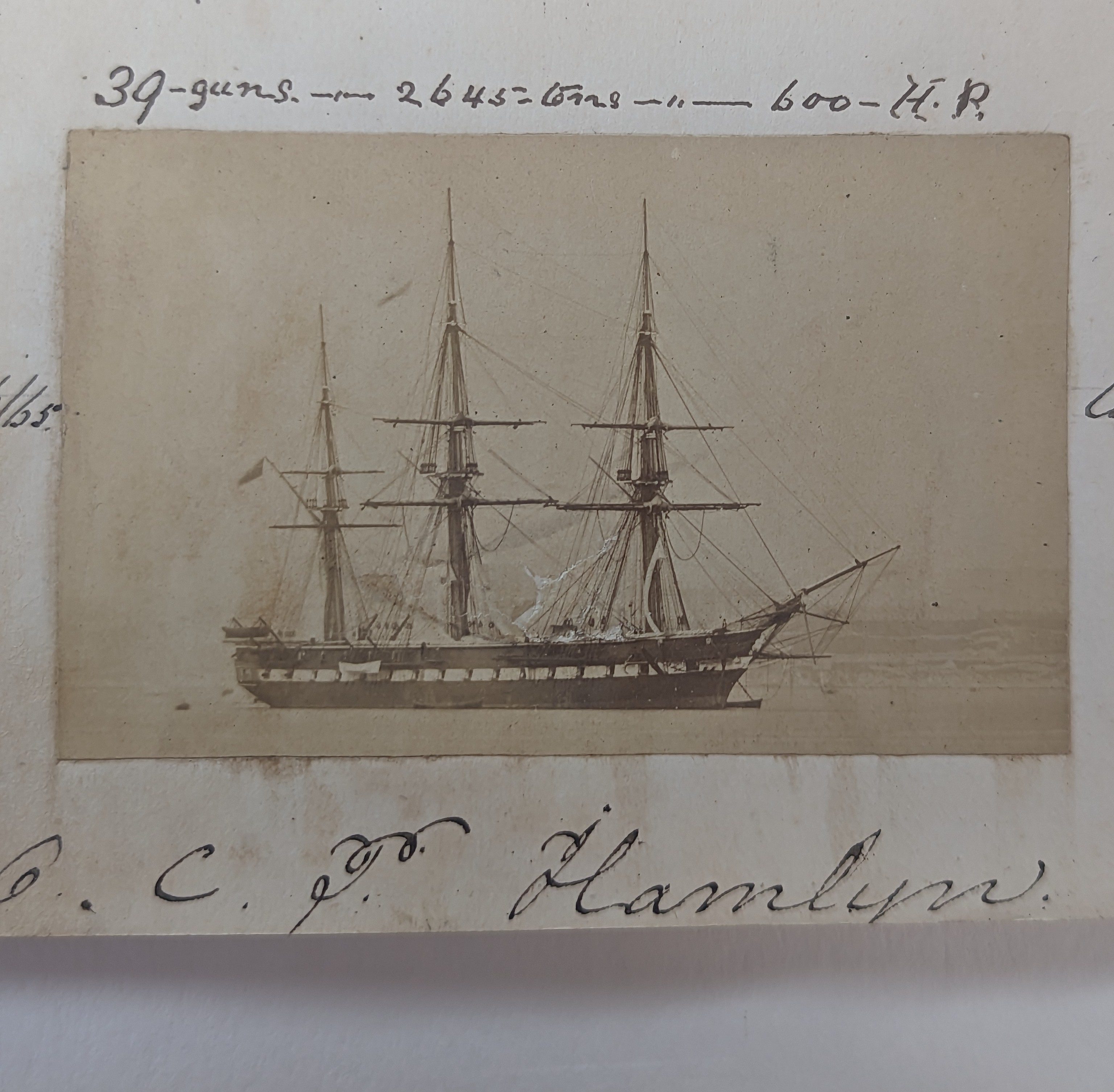

An albumen photograph of the HMS Liverpool had been pasted upon the title page of the textblock. A part of the image layer had torn, delaminated from the support, and then stuck back down in an incorrect spot. In order to correctly realign elements of the image, the misaligned area was carefully humidified using dampened blotter, with windowed polyester film used to protect the rest of the photograph. The image layer fragment was carefully manipulated back into the correct position with tweezers and adhered down with dry wheat starch paste.

Figs. 7 & 8 – Albumen photograph before treatment (left) and after treatment (right).

Areas of board delamination were consolidated with 5% methylcellulose. In areas of loss near the tail of the case, a small piece of thin photocraft card was inserted to provide support for cotton fibre infills. Losses in the parchment covering material were infilled using new parchment rather than Japanese tissue. Soft core Prismacolor pencils were used to tone the infills. While a similar tone could have been achieved with solvent dyes, they were not available in the studio, and leaving the parchment untoned would have made the repair very obtrusive. Colour reintegration with Prismacolor pencil on parchment does have a downside in that the colour lies upon the surface of the material rather than absorbing into the parchment. With the textblock consolidated and resewn and the parchment case repaired, the textblock is ready to be reattached to its case (Figure 9).

Reflection

The goal of the treatment was to prevent further loss of information and allow the book to be handled, while retaining original structural elements. Overall, the treatment was successful: the repaired textblock fits into the parchment case, and no extensions had to be made to the spine of the binding.

The main challenges in the conservation of this binding were handling the fragile textblock and discerning the original collation. As the spine area of the textblock was highly degraded, it was difficult to see where leaves had been torn out or removed during the book’s original use. It was important to observe all the clues, like intact spine folds and remnants of sewing, and to keep track of everything by drawing careful diagrams. Rushing this process would have led to mistakes. It was important to take the time to correctly identify how the signatures were put together. This extra step helped me do the object justice and gave me a deeper appreciation of nineteenth-century English stationery binding techniques.

All images by Clara Malinka, courtesy of the Admiralty Library.

Clara Malinka is a book and paper conservator who completed her MA in Conservation Studies from West Dean College in 2023. Since then, she has served as a project conservator at the Wellcome Collection and National Conservation Service.

Further reading

CUL Conservation (2021, 24th November). Mould damage and suction wedges: Conservation of felted paper in a bound iron-gall ink manuscript. Blog post, Cambridge University Library Special Collections. https://specialcollections-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/?p=22516

Jacobi, E. (2015) Moisture and mending: A method for doing local repairs on iron-gall ink. In Adapt & Evolve 2015: East Asian Materials and Techniques in Western Conservation. Proceedings from the International Conference of the Icon Book & Paper Group. London 8–10 April (London, The Institute of Conservation: 2017) pp. 80–90.

Middleton, B. (1963) A history of English craft bookbinding techniques. New York and London: Hafner Publishing.

Lovely repair.

LikeLike

beautifully done

LikeLike

Wonderful job, always very satisfying when a text-block fits back in after being repaired.

LikeLike