By Fatma Aslanoglu

As a conservator for the British Library Qatar Foundation Partnership, I have had the privilege of working on the conservation of a significant manuscript, Delhi Arabic 1905, also known as Miftāḥ al-Hisāb. In this post, I will share the details of the manuscript’s condition and of the meticulous conservation process I undertook, especially the conservation and reuse of the original endband.

Overview of the manuscript

Delhi Arabic 1905 is an Islamic manuscript written in Arabic, an 1819 Delhi copy of Jamshīd al-Kāshī’s fifteenth-century work Miftāḥ al-ḥisāb, based on a version derived from the author’s original. It deals mainly with the science of arithmetic and offers valuable insight into the history of mathematics. The manuscript contains 182 leaves organised into 30 gatherings, and is written on Islamic paper in carbon ink with some red pigment highlighting.

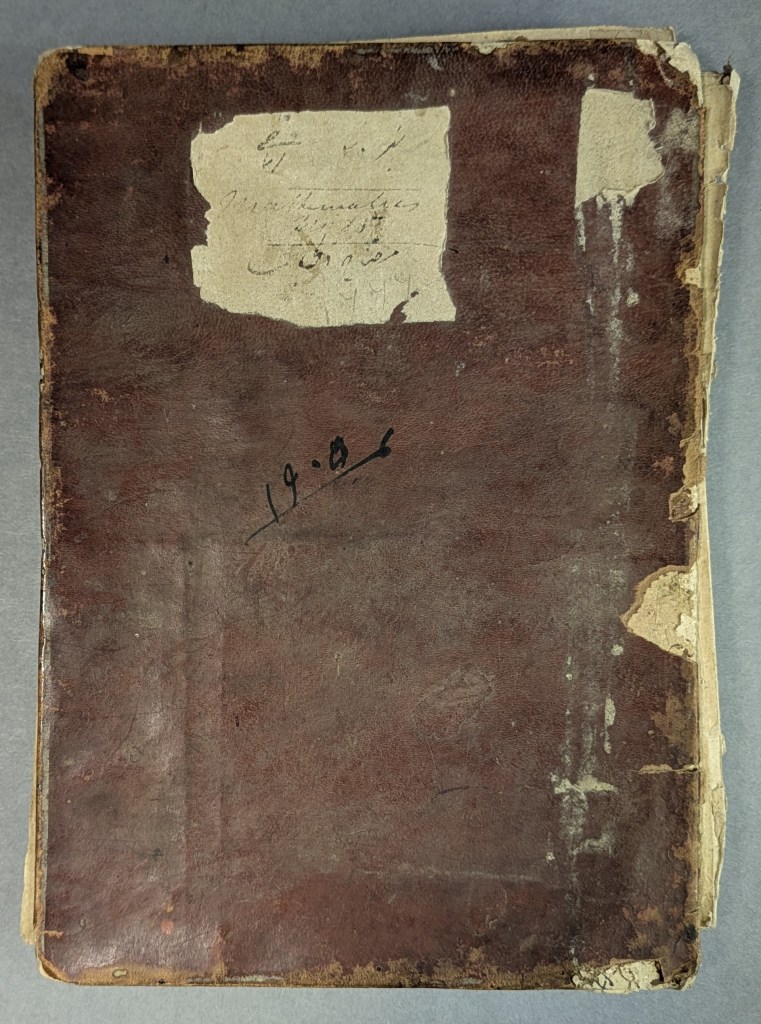

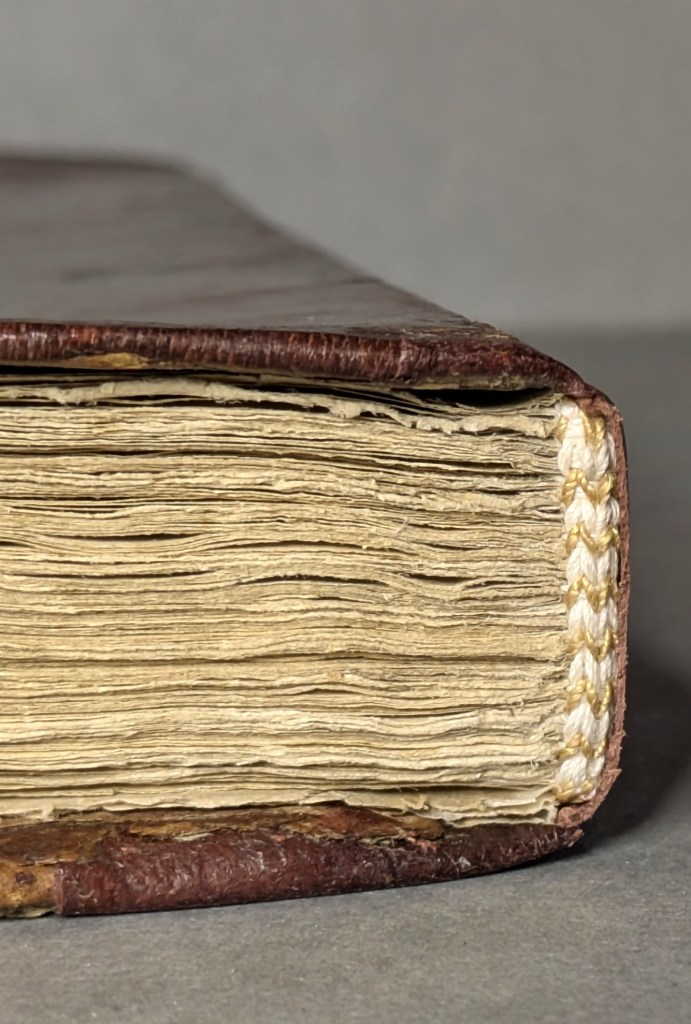

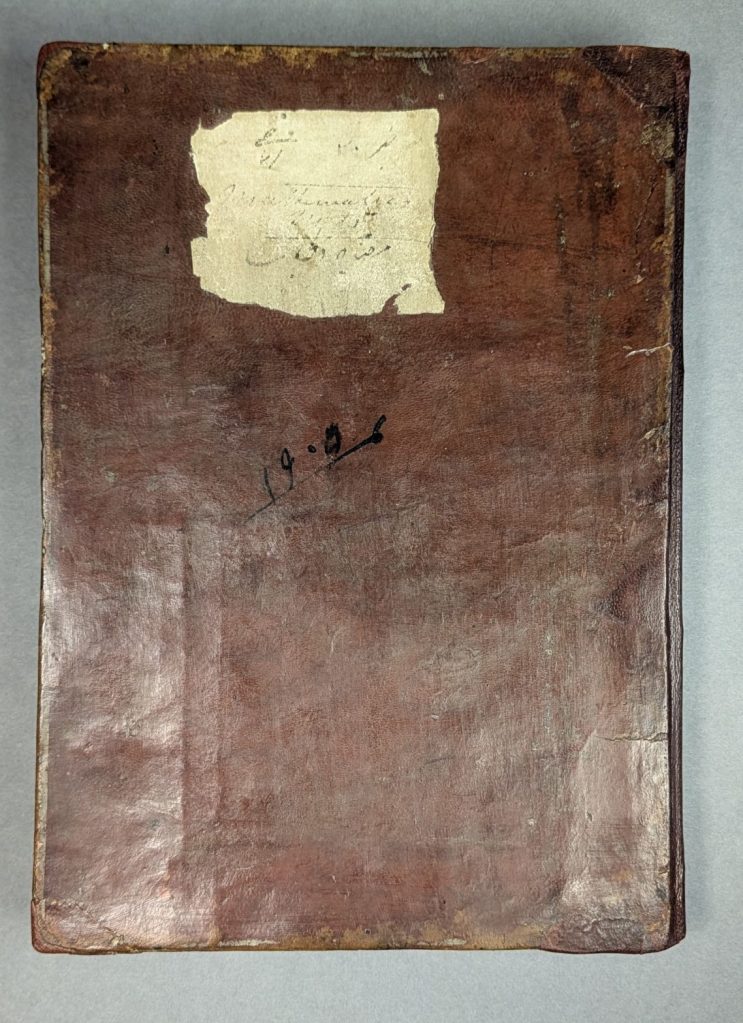

Like many historical manuscripts, this one had suffered significant deterioration over time, particularly in its binding. The cover was damaged, with detached boards, tears, and missing fragments. The leather spine was completely lost, compromising the manuscript’s structural stability. The text block was fragile, with loose sections, dirt, and evidence of insect damage, although the media remained in good condition. The tail endband was completely lost. Part of the headband was also missing, and the remaining section was damaged.

Fig. 1 – The damaged binding of the Delhi Arabic 1905 manuscript.

The importance of the endband

One of the challenges in conserving this manuscript was the preservation of the endband, a key part of the manuscript’s binding. The endband, a woven thread or cord structure at the top and bottom of the book, helps secure the pages to the cover, maintaining the overall integrity and functionality of the manuscript and helping it withstand wear and tear over the centuries. In addition, endbands are often decorated with intricate patterns that reflect the artistic traditions of the time.

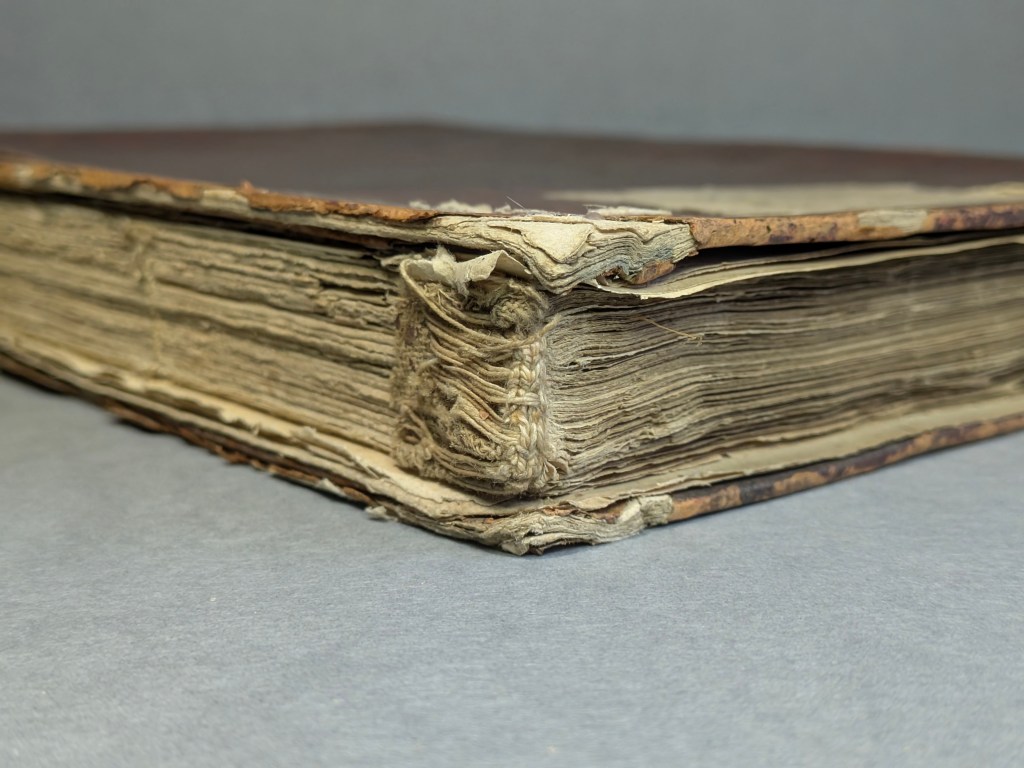

The chevron pattern in Islamic endbands: aesthetic and structural significance

The chevron pattern, a design consisting of V-shaped zigzag lines, is common in Islamic manuscript bindings. These patterns can be embroidered or woven into the endbands, and they serve both a structural and a decorative purpose. The geometric precision of the chevron design speaks to the technical skill of the binders and reflects the cultural and aesthetic values of Islamic art, which favours intricate, non-figurative designs.

Fig. 2 – Example of a chevron pattern endband.

Endband conservation: reusing the original endband

My conservation process focused on carefully conserving the original endband while also maintaining as much of the manuscript’s original material as possible. Here’s how I approached the conservation:

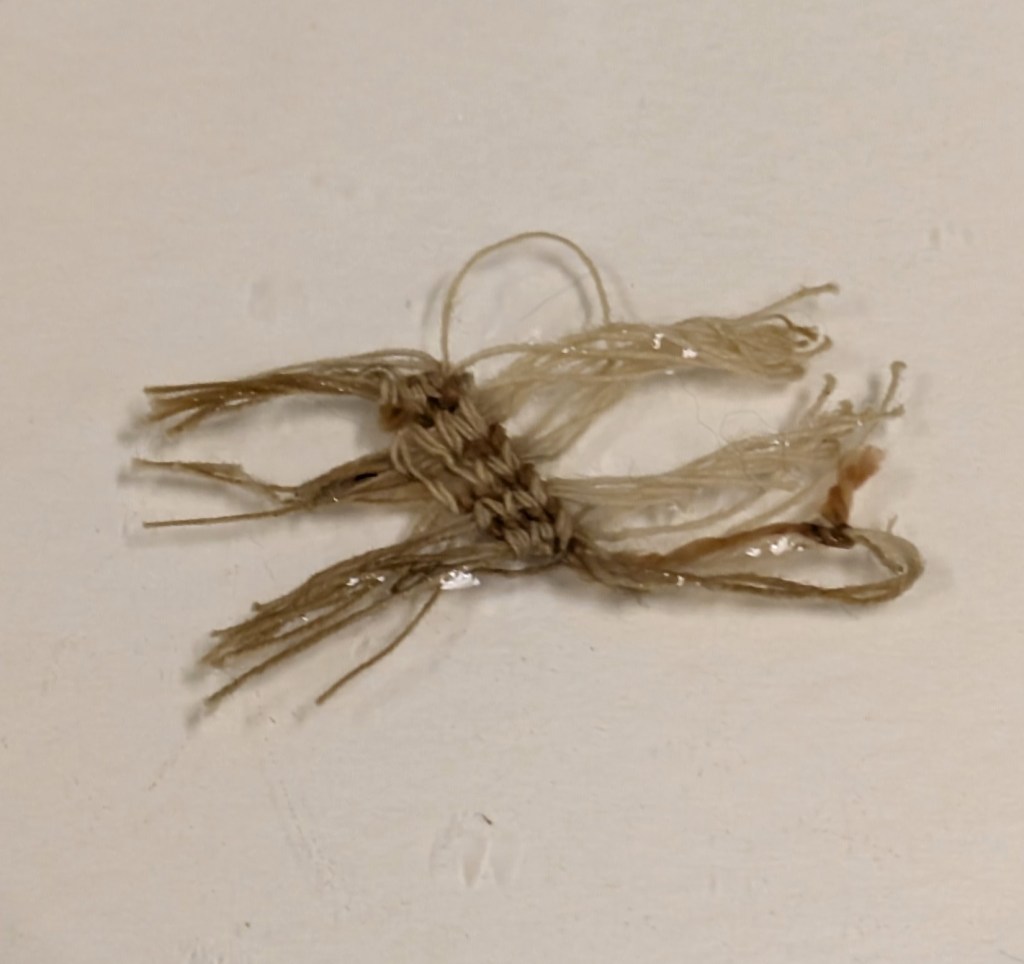

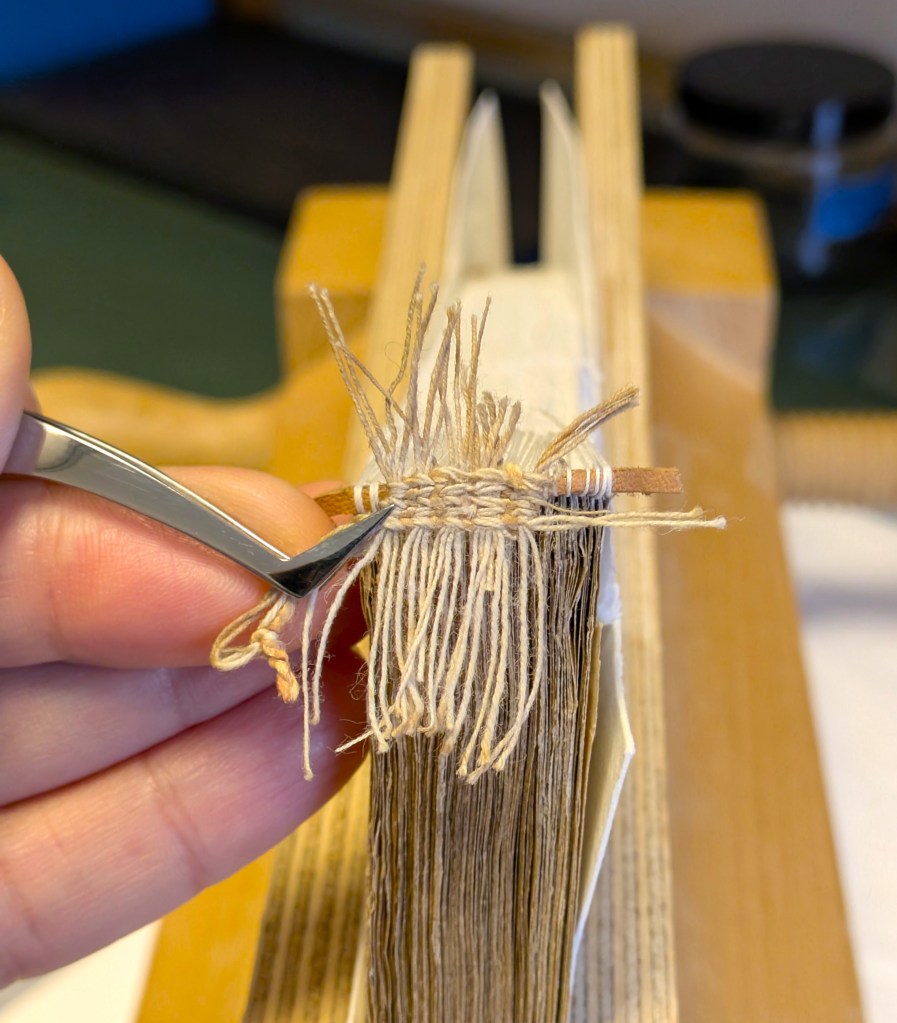

1. Removal and cleaning: The remaining head endband was gently detached for cleaning. Using lukewarm water, I carefully washed the endband to remove accumulated dirt and grime. This cleaning step was essential to ensure that no further damage occurred during the conservation process.

Fig. 3 – The detached endband during the washing process.

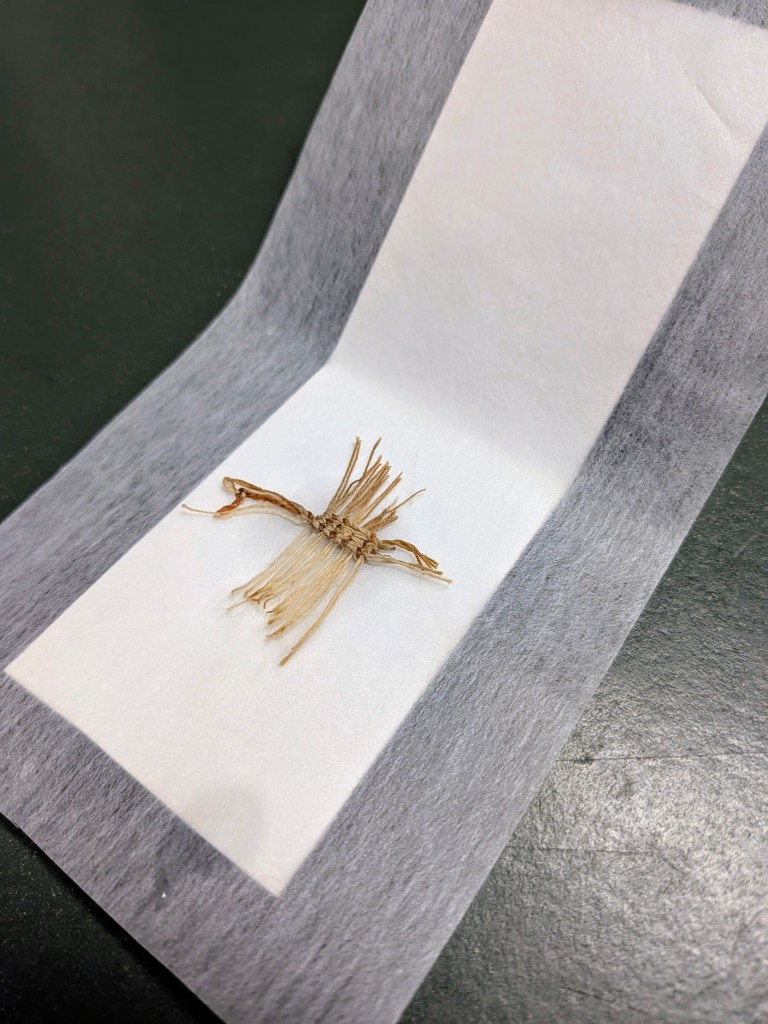

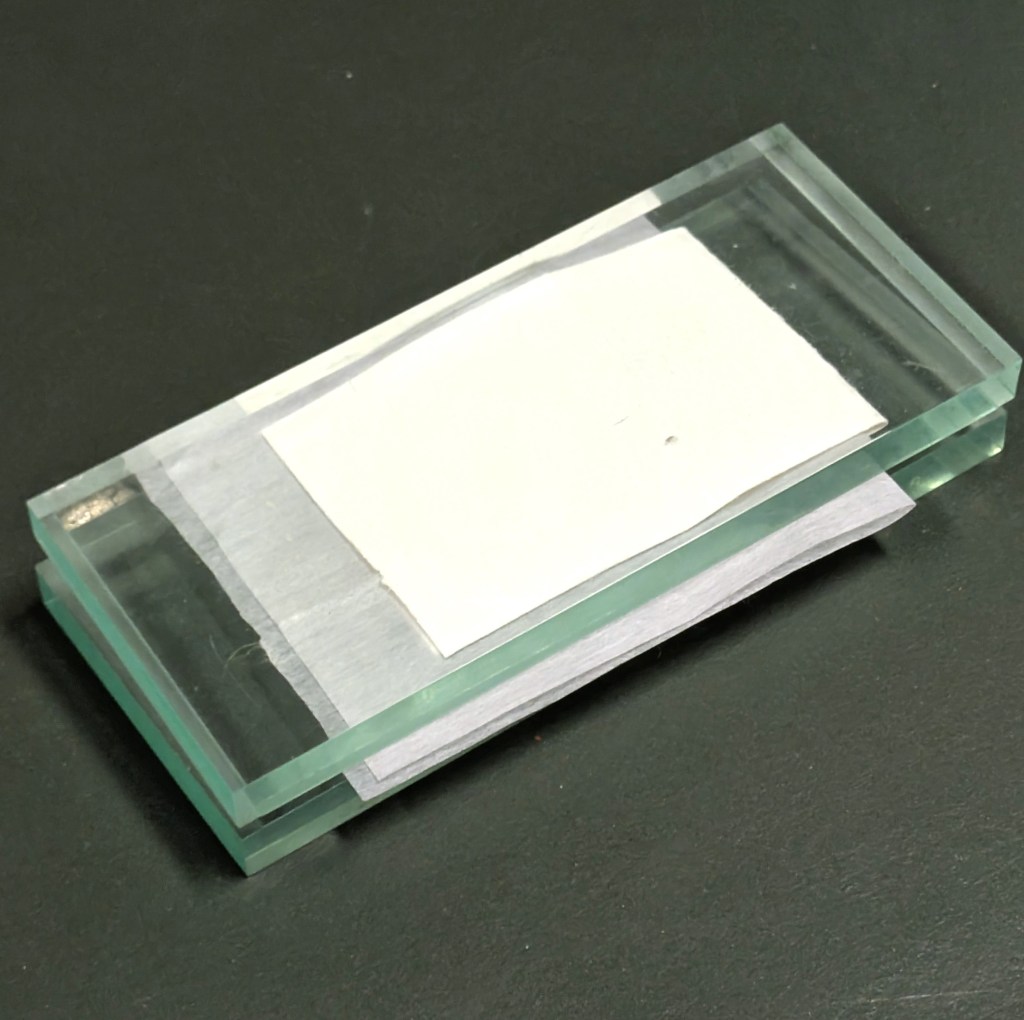

2. Drying and flattening: After cleaning, the endband was placed between blotting paper and Bondina (a smooth non-woven material) to absorb excess moisture and was then carefully flattened to retain its original shape. To avoid distortion and ensure even drying, the blotter sandwich was placed under two glass plates.

Fig. 4 – Drying and flattening the endband using Bondina, blotting paper, and glass weights.

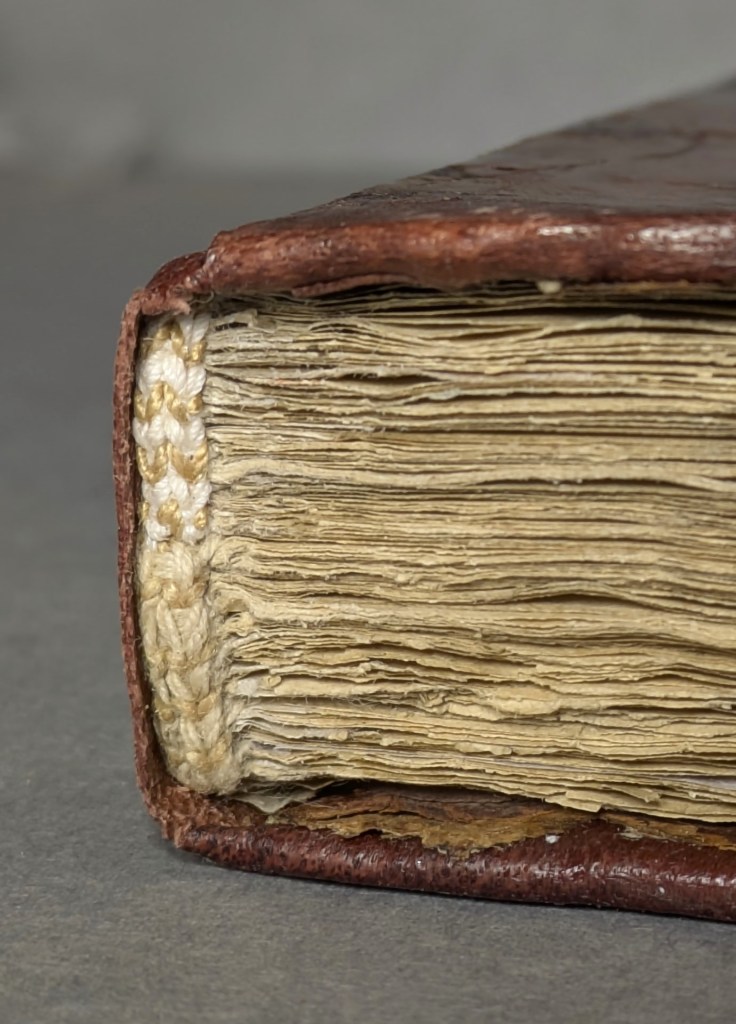

3. Reattachment and reconstruction: Once the head endband was completely dry, it was carefully reattached to its original position using wheat starch paste, ensuring both structural support and historical continuity. The upper part of the endband and the threads extending from its top were adhered directly to the text block’s spine. The primary endband, an additional structural sewing element that reinforces the spine, had been newly resewn to replace the original one which was beyond repair. It was sewn directly over the leather endband core visible in Figure 5, providing essential strength to the text block’s spine. Then the threads extending from the bottom of the head endband were adhered between the gatherings using wheat starch paste, ensuring they were properly integrated into the binding structure above the primary endband stitching.

Then I reconstructed the missing part of the endband by carefully weaving new threads that matched the existing pattern. This reconstruction was essential not only for aesthetic cohesion but also to reinforce the binding. To maintain overall stability, the text block’s gatherings were carefully aligned before being left to dry in position, ensuring that all components remained securely affixed and the manuscript retained its durability and integrity. I also reconstructed the missing tail endband by weaving a chevron pattern from threads that matched the existing endband and sewing it in place to ensure both functionality and visual continuity.

Fig. 5 – Reattaching the endband to its original position and reconstructing the missing part.

By reusing the original head endband and reconstructing the tail endband, I was able to conserve the manuscript’s functionality while preserving its historical authenticity. This careful balance between preservation and conservation ensures the ongoing cultural connection between the manuscript and its past.

Fig. 6 – Detail of the reattached endband and reconstructed missing part.

Other repairs

The conservation treatment of the manuscript also included a detailed condition check, photo documentation, dry cleaning, and careful tear repair and infilling using Japanese tissue. I resewed the text block with mixed cotton/linen thread and created new primary endbands.

Additionally, I repaired and reattached the detached leather boards. Since the original spine was completely lost, I added a new spine lining and a leather spine to reinforce the manuscript’s structure. These steps further contribute to the manuscript’s overall preservation.

Fig. 7 – After treatment. Tail endband detail (top left), head endband detail (top right).

Results and reflections

The conservation of the Delhi Arabic 1905 manuscript was successful in terms of both structural stability and preserving its historical and artistic value. By reusing the original endband and reconstructing the missing tail endband, I ensured that the manuscript retains its integrity and usability for future generations.

The conservation of the manuscript reminded me of the deep responsibility that we, as conservators, have to preserve not just physical objects but also cultural legacies. Our careful conservation ensures that invaluable works continue to inspire and educate future generations.

By reusing the original endband and following traditional techniques, I helped maintain the link between the past and the future, ensuring the manuscript’s historical integrity. This conservation effort not only protects a piece of history but also allows future generations to appreciate the craftsmanship, knowledge, and artistry of the past.

All photographs by Fatma Aslanoglu, courtesy of the British Library.

Biography

Fatma Aslanoglu is currently working at the British Library as the Gulf history and Arabic science conservator, where she specialises in preserving rare manuscripts and historical materials. With a decade of experience in book and paper conservation, her expertise is primarily focused on Islamic manuscripts and other significant archival materials. Fatma holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Traditional Turkish Arts (Illumination-Miniature, Main Art Branch) from Marmara University. She has also pursued advanced studies in the same field at Mimar Sinan University. Her studies included a conservation module, leading her to integrate conservation techniques into her artistic practice, which later shaped her professional career in cultural heritage preservation.

Previously, Fatma worked as a project conservator at University College London (UCL) Special Collections and as a freelance conservator at Codex Conservation. In these roles, she gained valuable experience conserving a diverse range of historical documents, including Islamic manuscripts, medieval parchments, early printed books, and modern archival materials.

Earlier in her career, Fatma worked as a book and paper conservator at the Süleymaniye Library, where she made significant contributions to the preservation of numerous Islamic manuscripts. This experience further refined her expertise in manuscript conservation and deepened her commitment to the preservation of cultural heritage.

To find out more about Fatma’s work, follow her on Instagram: @f.aslanoglubookconservation

Well done. Looks like you have done a great job with it.

LikeLike

Many thanks, Roger! I appreciate your kind comment.

LikeLike

Very nice result!

It looks very well attached to the original.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment Rita! I really enjoyed working on that part.

LikeLike

What a great approach to re-integrate a substantial fragment of the endband. It certainly seems more satisfying than “bagging” the fragment which would be retained with the ms. Did you also make a box for long-term storage? Thanks! bryan

LikeLike

Thanks so much, Bryan! I completely agree. Reintegrating the fragment felt much more meaningful than keeping it aside in a separate bag. It’s now safely housed in a proper archival box for long-term care. Really appreciate your kind words!

LikeLike

Very very interesting and well done, may I ask if you add some stitches to “sew” the portion of the original endband to the book block, or were the original threads extending from the top just adhered on the spine (both ends?)

thank you

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Paola, for your kind words!

The threads extending from the top of the original endband were adhered directly onto the spine, and the threads from the bottom were pasted between the gatherings using wheat starch paste. No new stitching was added. I briefly mentioned this in the section about reattaching the endband. I’m really happy you found it interesting!

LikeLike