By Alexandra Hill

One of the most rewarding things to find in a rare book is waste material. This term refers to recycled paper or parchment, often with printed or manuscript text, that was used in the construction of historical book bindings. It can be visible as part of the outer binding, used as flyleaves or hidden beneath the boards. As part of the ongoing inventory of the pre-1851 printed rare materials at Wellcome Collection, we are recording evidence of waste material as we go along. This will improve the catalogue and create opportunities for further research. Here is a sneak peek of some of our findings.

Researchers are increasingly interested in what waste material can reveal about the history of rare books and of the printing and bookbinding trade. The materials in these bindings are sometimes unique, and they can offer insight into texts which, ironically, survived by being thrown away. Often it is only when the binding is damaged or is being repaired that this evidence is revealed.

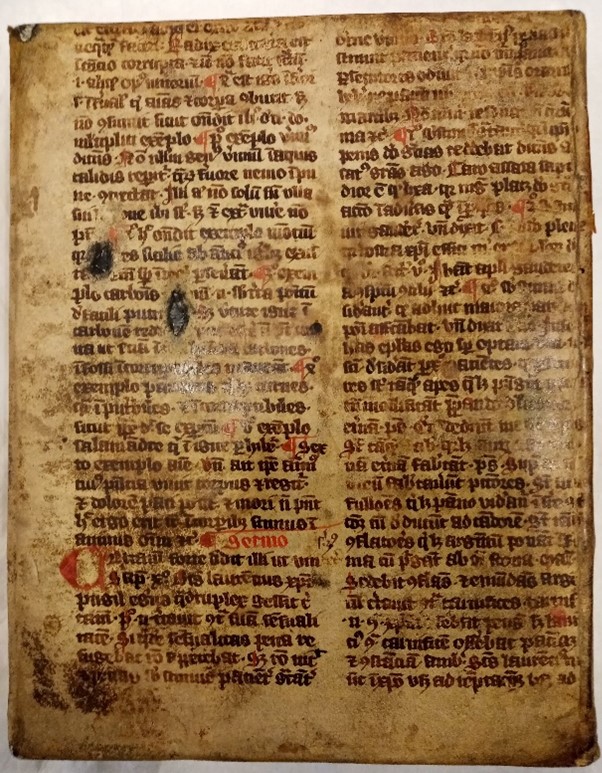

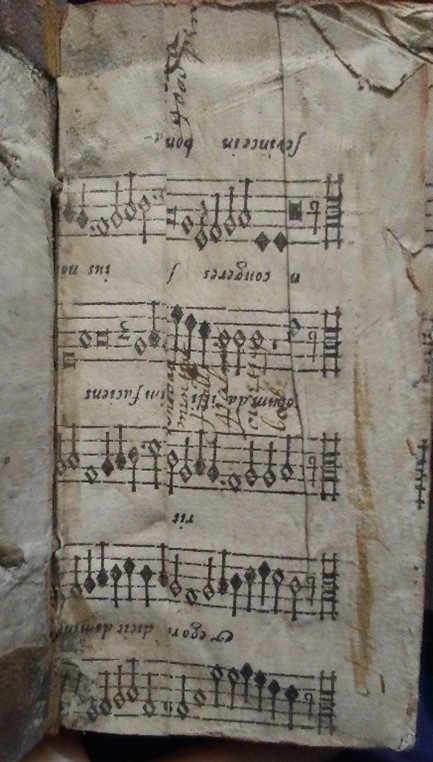

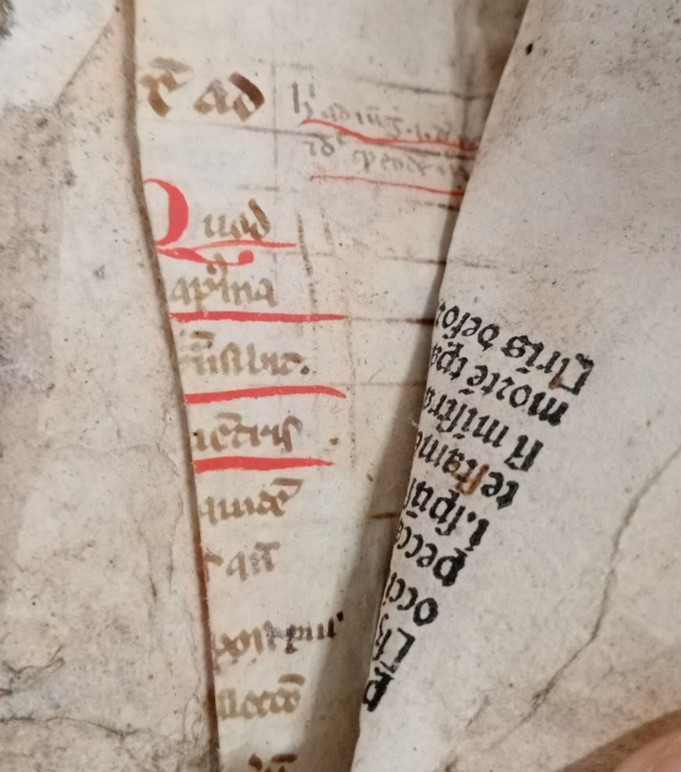

Fig. 1, 2 – Examples of waste material in Basilica chymica ([1623]) EPB/B/1677/1 and A map of the microcosme (1642) EPB/A/15685. The first example is a leaf from a mediaeval Latin manuscript, possibly thirteenth-century, being used as a cover. The second is a page of early-seventeenth-century printed musical notation for a hymn based on the Book of Romans. There are multiple pages of this musical notation being used as flyleaves at the front and back of the text. Photography by Alexandra Hill; courtesy of Wellcome Collection.

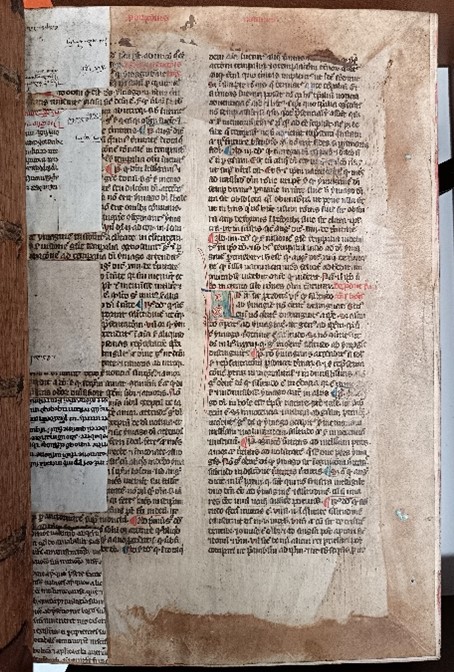

Waste material can reveal how material was reused and how books were constructed. In Wellcome’s copy of Lexicon graecolatinum (Basle: H. Curo for H. Petrus, 1548, Fig. 3), you can see the parchment waste material used for support between the sewing cords. You can also see the stain from where it was pasted down onto the board.

The parchment is covered in Latin text which, fortunately, has a clear running title at the top of the page: ‘De [co]gnitione anime sep[ar]ate’. This is likely a manuscript commentary on Aristotle’s De Anima [On the Soul] by Thomas Aquinas, possibly from the thirteenth or fourteenth century. There is also parchment from another manuscript in a different, likely earlier hand, with corrections and marginalia, acting as supports. Wellcome’s copy of Lexicon graecolatinum was bought from Steven’s auction house in 1923, and, unsurprisingly, there is little recorded information about the waste material except that it is from an ‘early’ manuscript.

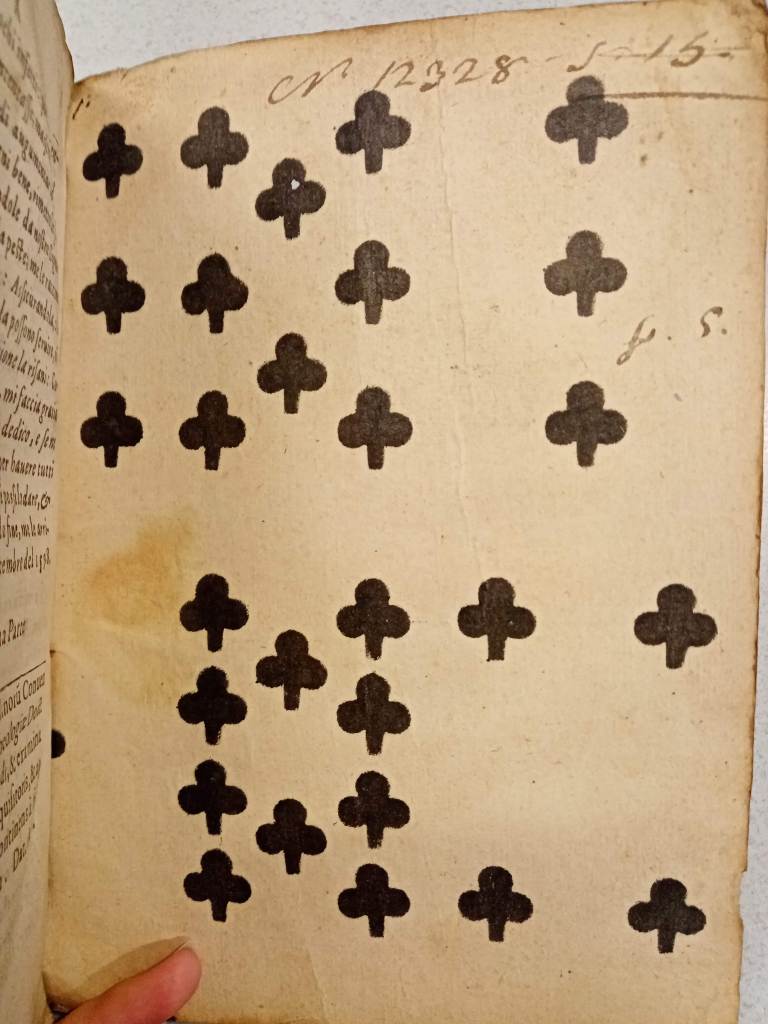

Waste material can show us what kind of material was lying around in early modern bookbinding workshops, and it was more than just mediaeval manuscripts. Wellcome’s copy of Trattato di peste (Asti: V. Giangrandi, 1598) is intriguing because the waste material in it is an uncut page of printed playing cards. Playing cards are highly ephemeral items that rarely survive, so it is exciting to find an example in such an unusual place. On this sheet, different numbered cards have been printed side by side. The book was printed in Asti, in northern Italy, and the design of the card suit suggests that it was also likely bound in the same area. That part of Italy, Piedmont, used the French-style clubs suit, similar to what we recognise as clubs today, whereas further south, the equivalent card suit would have had a baton or cudgel design.

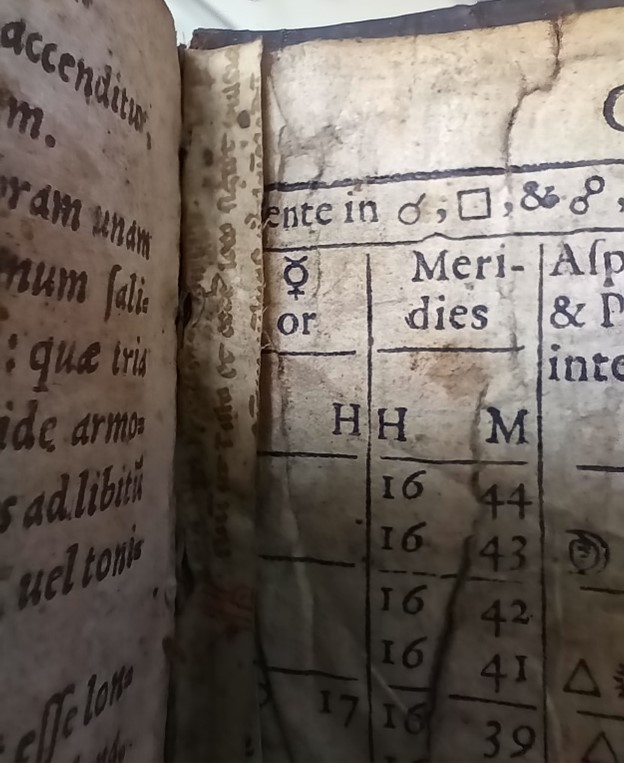

Some examples even show a mix of materials from multiple sources in the same book. One of Wellcome’s copies of De secretis mulierum libellus ([Lyons?]: [publisher not identified], [1566]) has both printed and manuscript waste material hidden within the binding. Because the fragments are small and lack a caption title, it is difficult to identify the source text. One fragment of printed Latin text appears to be from a religious commentary. The fragment has two sections of text, with the biblical text in larger gothic type and the commentary in smaller type to the side. Part of the biblical text refers to the son of Moses, while the commentary refers to conversion and persecution. The other fragment of printed text is from an ephemeris, a book which predicted the movement of the planets over the year. Ephemerides are another highly ephemeral item, as they covered a single calendar year and soon went out of date. The manuscript is more difficult to identify than the printed texts, as it is only visible in the gutter and most of it is covered with the printed pastedown.

Fig. 6, 7 – Waste material in De secretis mulierum libellus [EPB/A/139/2]. Bought at Stevens Auction with two other items on 12/9/22. Lot 401. Photography by Alexandra Hill; courtesy of Wellcome Collection.

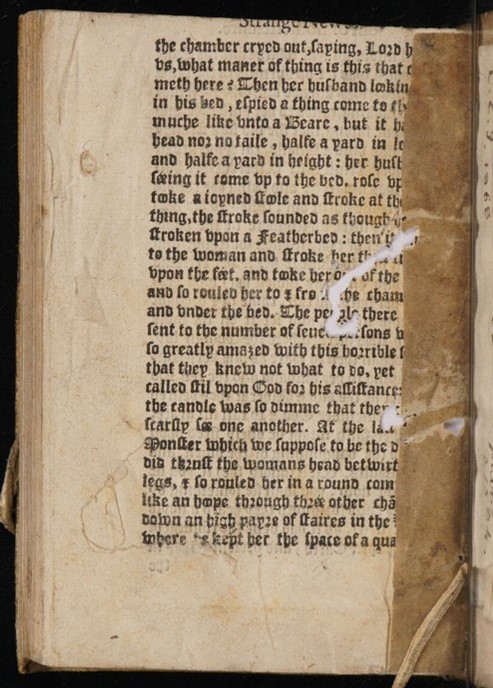

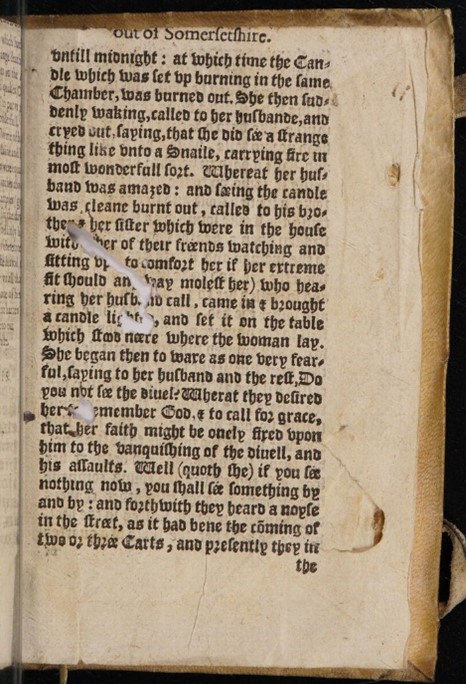

These examples show how waste material can preserve items that generally have low survival rates. Strangely, being used as waste material is sometimes the main reason a text survives. One such example has been identified and catalogued at Wellcome. Fragments of A true and most dreadfull discourse of a woman [Margaret Cooper] possessed with deuill; who in the likenesse of a headlesse beare fetcher her out of her bedd … on the fower and twentie of May last. 1584, at Dichet in Sommersetshire, a pamphlet published in 1584, were discovered as waste material in an edition of The treasury of Health from 1585 and catalogued as a separate item bound in the same volume. This shows how transient such a pamphlet was – within a year of publication, it was already used to bind new books in a different printer’s workshop. This was not unusual. In my analysis of lost books – ones that cannot be traced to an existing copy – printed in early modern England, I found that newsprint on events in Britain had a lower survival rate than news on events on the continent and further afield. According to the English Short Title Catalogue, an international online union catalogue of books printed in British languages, there is only one other recorded copy of the pamphlet in the world, stored at the British Library [C.27.a.6.].

The pamphlet was printed for bookseller Thomas Nelson, while the book it was used to bind was printed by Thomas East. Even though there was no direct link between the bookseller and printer, they both had workshops near the London bookbinders’ district, within walking distance of each other. They were also both members of the Stationers’ Company, which held a monopoly over the printing industry in London during this period. Even though it is not clear who bound the book, and whether it was done in house or by an independent bookbinder, it is not difficult to imagine how the pamphlet and book might have come together in such a close-knit industry.

Fig. 8, 9 – The pamphlet A true and most dreadfull discourse of a woman [Margaret Cooper] possessed with deuill (EPB/A/4957.2) used as waste material in another book. The clear caption title at the top, ‘Strange news out of Somersetshire’, helped identify the pamphlet, as did the fragment of the dedication to the reader. The book was bought with seven other works from Maggs Bros in August 1906. Photography courtesy of Wellcome Collection.

Waste material is a fascinating topic that brings together aspects of history, cataloguing and conservation. It is important to record and preserve this unique material as we find it. Books should be photographed while they are being repaired, and any material removed should be stored alongside the book. This way, the historical connection is preserved. Wellcome has already recorded 3072 catalogued items with waste material, and those are just the books where the material is visible. Who knows how many more treasures remain hidden under the boards.

Alexandra Hill is the librarian, printed rare material, at Wellcome Collection in London. She is responsible for the inventory of all the pre-1851 printed and published rare materials at Wellcome, and her interests lie in the materiality of books and their history as objects. Her latest book chapter, ‘Transience and Loss’ in Adam Smyth (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the History of the Book in Early Modern England, focuses on how book survival and loss have shaped our understanding of early modern books.

I’ve often wondered why this material is called waste or “binder’s waste”. The materials themselves were good enough quality to be reused, isn’t is closer to primary recycling? Jeff

LikeLike

Thanks for reading Jeff. Yes, the materials could be in really good condition. There is evidence that some agents acting for collectors in the early modern period would assemble collections of ballads from booksellers’ waste stock. This then raises the intriguing question over how far these ‘waste’ printed items that survive in modern-day collections represent what was actually being read/used to destruction during the period.

LikeLike