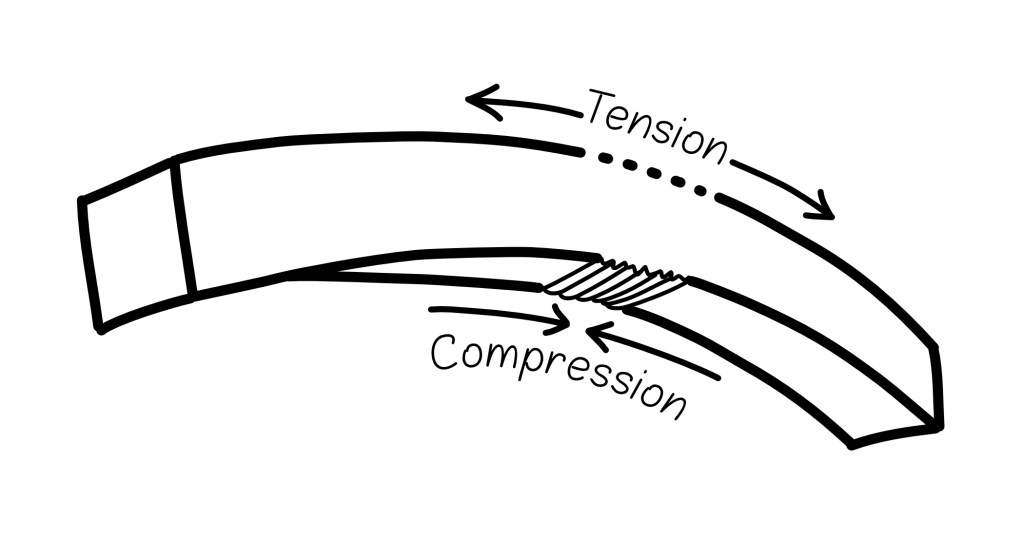

Part I of this article explored the mechanical principles that govern a book spine and how our choice of spine lining materials affects the stresses that occur when a book is opened. We learned that when any material bends, there is a tension side and a compression side (Fig. 1). Material in the tension layer will spread apart, while material in the compression layer will, as the name suggests, compress. This principle always applies when a book is opened, regardless of binding type. The tension layer consists of the spine folds of the text block (the folded edges of the text sections) and the material adhered directly to them. All materials placed on top of this layer are in compression.

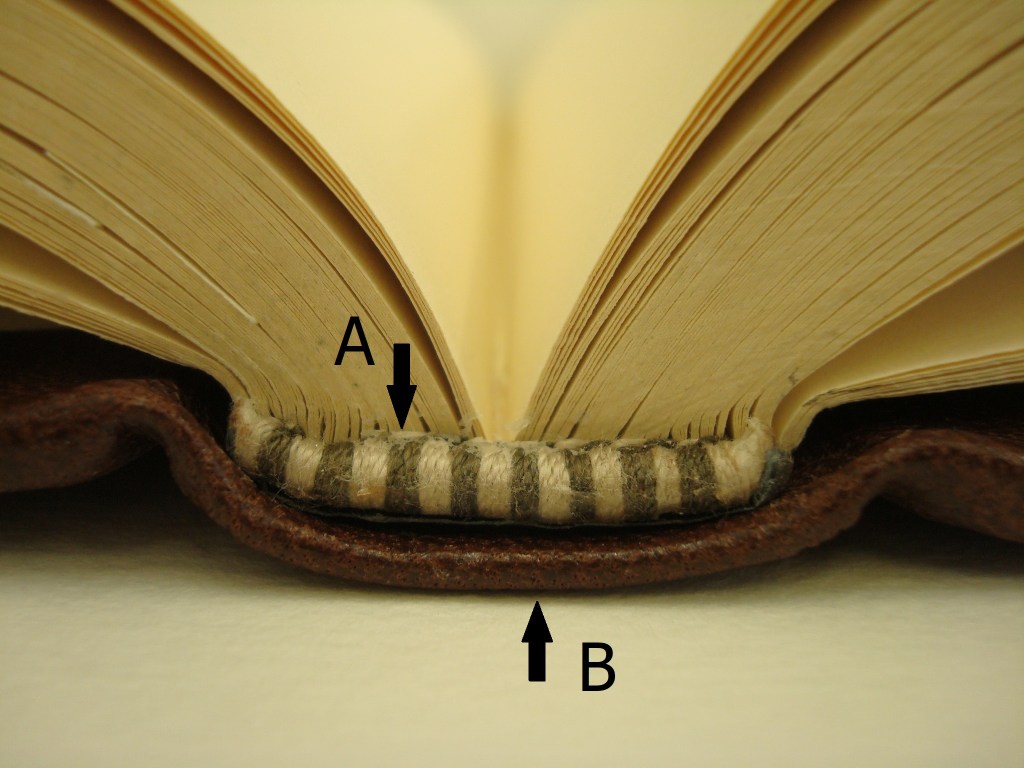

Figs. 2, 3 – Tension (A) and compression (B) layers: the tension and compression principle applies to any open book, regardless of the binding type. Photography by Paula Steere.

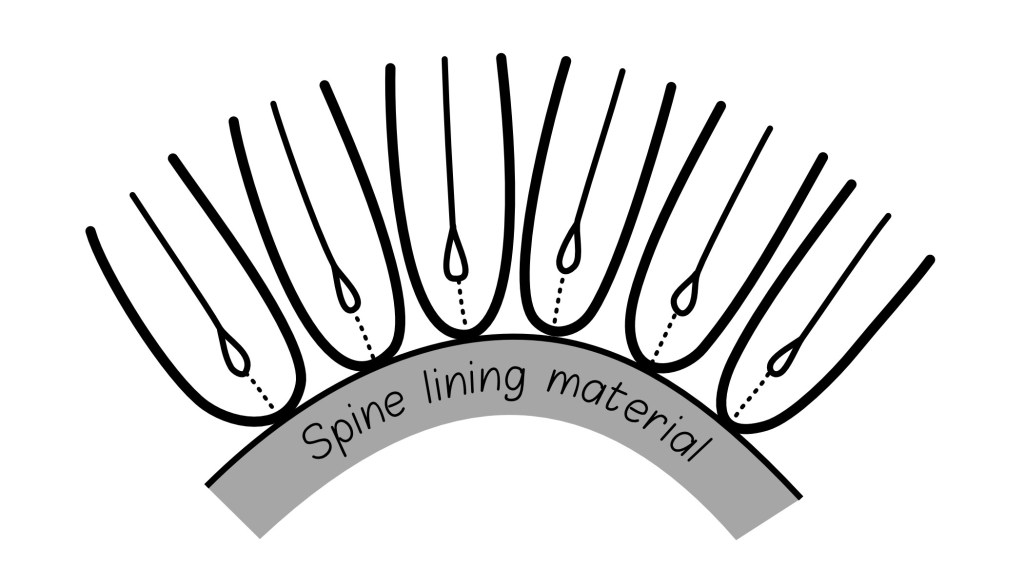

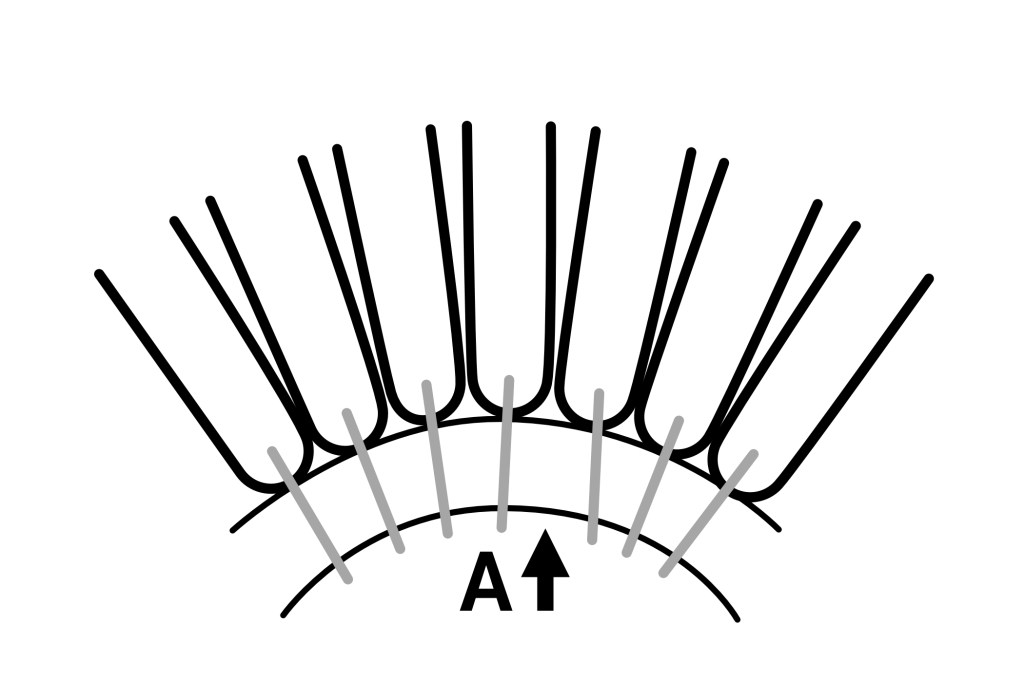

Part I also discussed the movement of the spine folds when a book is opened. This movement is largely imperceptible, but critical to spine function and durability. Too much movement could contribute to poor opening and structural failure. We also do not want to prevent movement entirely, as the spine needs to flex somewhat to open well. Each of the spine folds moves with some degree of independence. This localised movement can be thought of as a series of flexible mini-bends (McIlvaine 2017a), as illustrated in Figure 4. These mini-bends have different radii and are also affected by adhesives and sewing. This creates non-uniform stiffness, which leads to localised strain (deformation) (Fig. 5). It is this localised strain that causes the spine to fail.

Spine linings also move, and these shearing forces contribute to the deformation of the spine folds. The choice of lining materials affects the extent of the deformation. Miller (2010, p. 100) defines linings as a support that allows the spine to flex ‘without the sewn sections parting’. While in reality we cannot eliminate deformation entirely, informed choices can minimise it. Part I illustrates in detail a fundamental aim of spine linings: to minimise deformation at the text block and first layer interface (the spine folds and the first lining in the tension layer). Put simply, we want to minimise the spreading apart (deformation) of the spine folds. Our choice of spine lining materials will impact this. Common spine lining materials were explored – paper, linen, cotton, leather and adhesives – and their mechanical properties that make them more or less suitable for spine linings based on these engineering principles. The first step in the spine lining design presented in Part I is to place a stiff and thin first lining against the spine folds to minimise movement. Linen was suggested for the first lining because it is a relatively stiff, strong and uniform material due to the properties of the raw material and the way it is manufactured. All subsequent materials make up the compression layer, which should ideally be less stiff than the tension layer – no easy task. The compression layer includes further linings, adhesives and covering material. Cotton is a good choice for additional linings in the compression layer because it is less stiff than linen and also a strong material for reattaching boards. Leather, a strong but supple material, was also explored in Part I as a second lining because of the strength of collagen. Paper is not as strong or uniformly stiff due to the random formation of fibres during manufacture; therefore, it is less suitable for linings.

Mechanics of sewing structure

Ultimately, the aim is to create uniform stiffness throughout the spine so that when a book is opened, the strain (deformation) is distributed evenly in the arch that forms. This concave arch is called throw up (Ligatus no date). The degree of spine stiffness affects throw up, and the degree of throw up contributes to how well a book opens, including whether the pages lie flat (which is desirable). (The type of paper and grain direction also have a great impact on the latter, but are out of scope of this article.) Overall spine stiffness is a combination of lining materials and sewing structure. Part I discusses how our choice of spine lining materials can help achieve a uniform arch by minimising the movement of the spine folds. Part II explores how sewing structure contributes to uniform spine stiffness (uniform arch), specifically sewing on tapes and raised cords.

First let’s consider sewing supports. We can use the same engineering principles that we applied to lining materials to understand their contribution to stiffness. For example, the thicker the sewing supports, the stiffer they will be when bending due to the neutral axis principle (McIlvaine 2017c; Fig. 6), which we encountered in Part I. The neutral axis principle is analogous to bending a piece of cardboard versus a piece of paper – there will be more damage (deformation) to the cardboard because of its greater thickness. To put it another way, a small-diameter cord contains less strain (deformation) than a larger-diameter cord when bent at the same radius and angle. (The same applies to thread, and so on.)

However, the size (diameter) of the cord relative to the thickness of the spine must also be considered. For example, imagine two books with identical cords. The first book is 1 cm thick and the second is 4 cm thick. When the books are opened to an equal opening angle, the thinner book’s cords contain more strain per unit length. This is because the strain is distributed over 1 cm of cord, whereas in the thicker book, it is distributed over 4 cm of cord (McIlvaine 2022a). To my knowledge, there is no simple formula for calculating the thickness of the cords relative to the text block. There are too many variables; for instance, the type and amount of adhesive, thickness of paper, thread tension and so on. This is where experience and observation come into the equation.

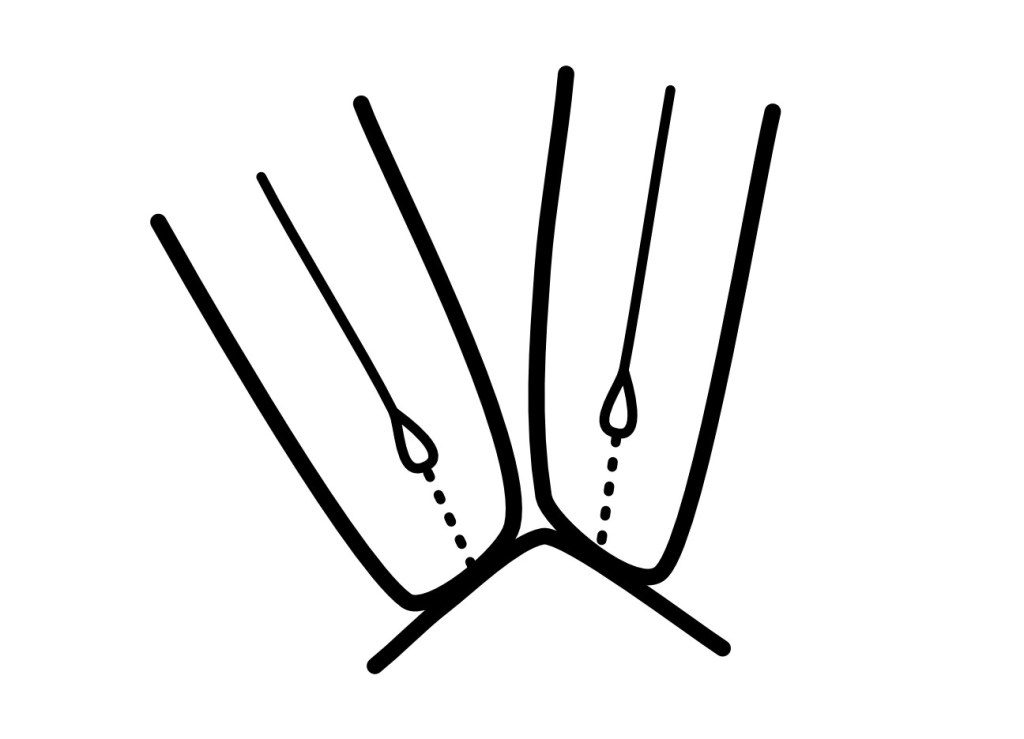

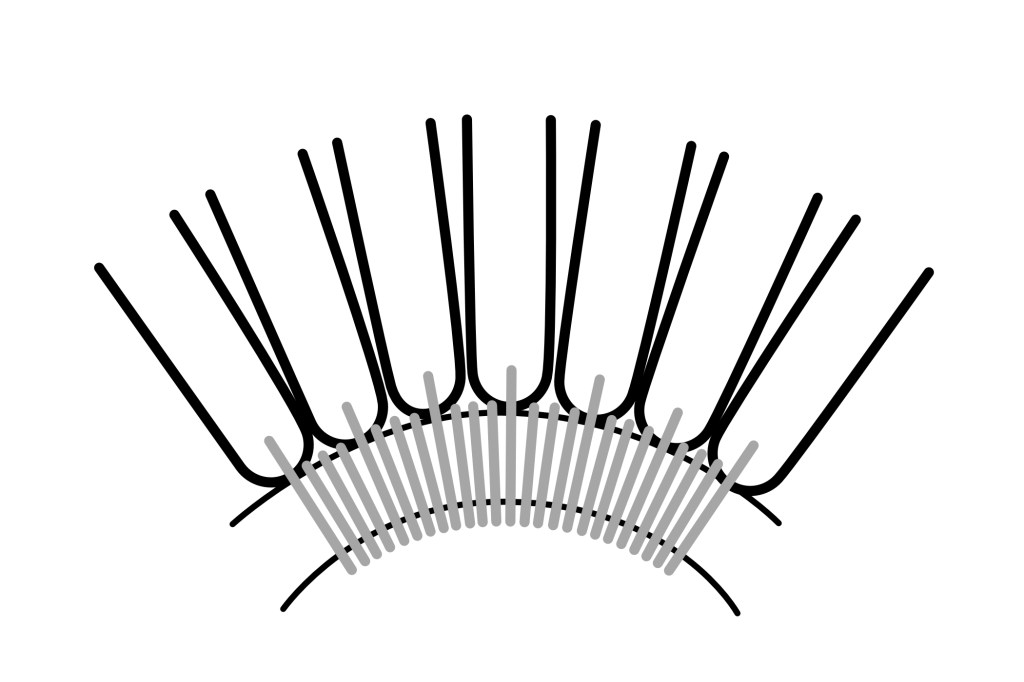

Sewing structure also affects the stiffness of a book spine, and there are a few factors to consider to help control overall spine stiffness. Unpacked sewing on tapes or cords contains gaps between the threads (Figs. 7 and 8). This creates uneven strain with areas of local high and low stress (McIlvaine 2017e). Packed sewing (Figs. 9 and 10), or what Conroy (1987) calls loop sewing, minimises abrupt changes in bending stiffness and creates a more uniform bend (and uniform stiffness, which is the goal). Franck (1941, p. 7) is credited with first recording what he termed the ‘supreme method’ of packed sewing, noting that this technique prevents the cord from bending at a sharp opening radius, which is an area of high stress concentration (Fig. 11). The mini-bends discussed earlier will be less pronounced in packed sewing. The uniform curve created by packed sewing can also help to protect the spine leather and tooling on a tight back.

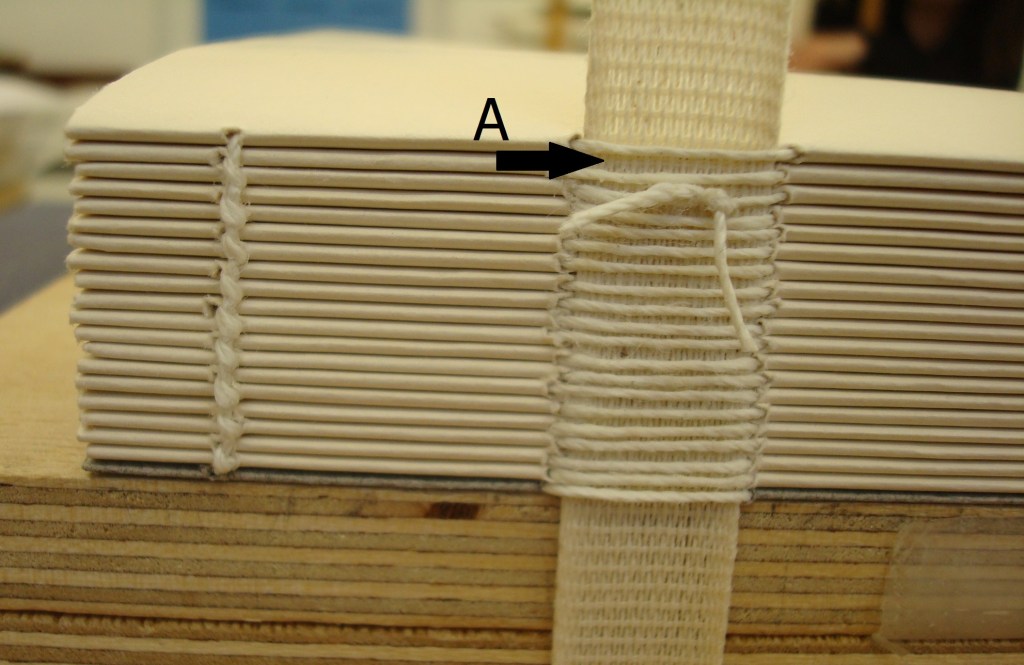

Figs. 7, 8 – In the examples above, high strain occurs in the gaps between threads as shown at A. The high-strain areas are where the mini-bends occur (non-uniform strain) (McIlvaine 2022b). Drawing by Paula Steere; digital rendering by The Book & Paper Gathering; photography by Paula Steere.

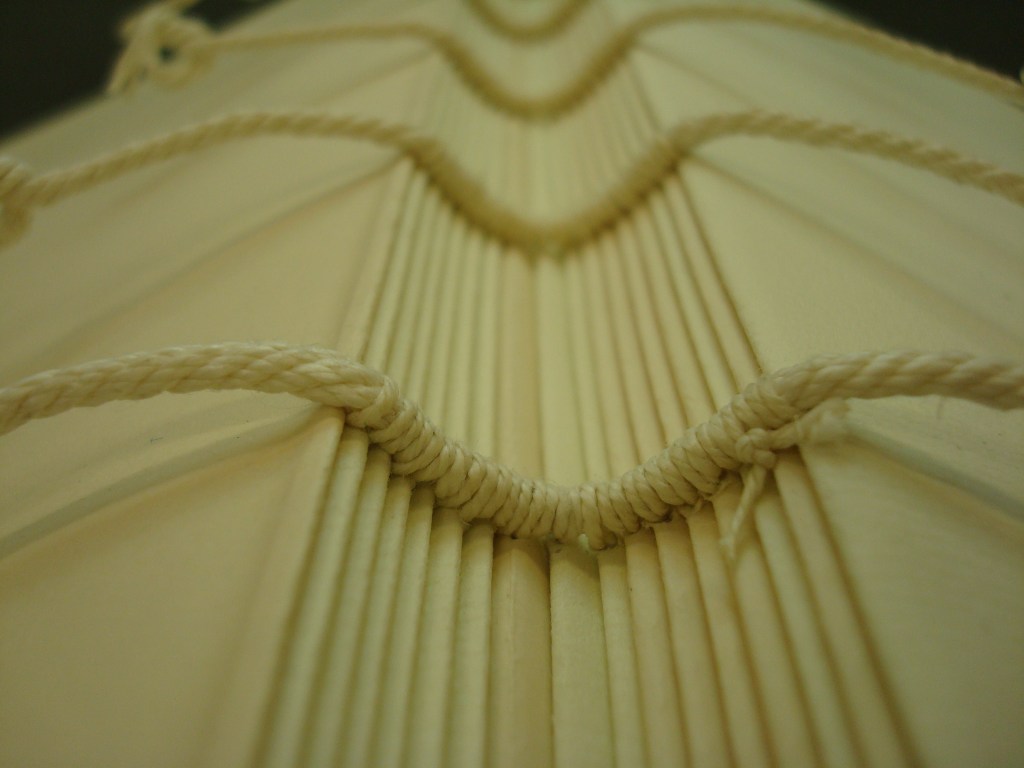

Figs. 9, 10 – Packed sewing reduces the degree of localised strain because it creates more uniform bending stiffness. Note there are no linings or adhesives on this text block, and we can clearly see the movement of the spine folds in the centre sections. This is caused by the high localised strain between the spine folds when the text block is opened. Linings of appropriate design will help minimise this movement (McIlvaine 2022b). Drawing by Paula Steere; digital rendering by The Book & Paper Gathering; photography by Paula Steere.

Herbert (2012) compared the effect of different sewing structures on what he termed ‘book action’. His excellent article is available online and contains images of binding models that illustrate these engineering concepts. Interestingly, his project was inspired by Conroy’s The Movement of the Book Spine (1987), where my own research began. Herbert created four tight back leather binding models using the same thread, paper (Mohawk, a relatively stiff paper, according to the author), adhesive and number of sections with the same number of folios in each section. Each model was rounded and backed to a 90° shoulder. Two types of sewing supports were used: tapes and cords. One model was sewn over tapes (as in Fig. 8); one used unpacked sewing around single raised cords (as in Fig. 7); one used packed sewing around single cords (as in Figs. 9 and 10); and one model was sewn on double cords, which are two cords side by side (with a herringbone stitch).

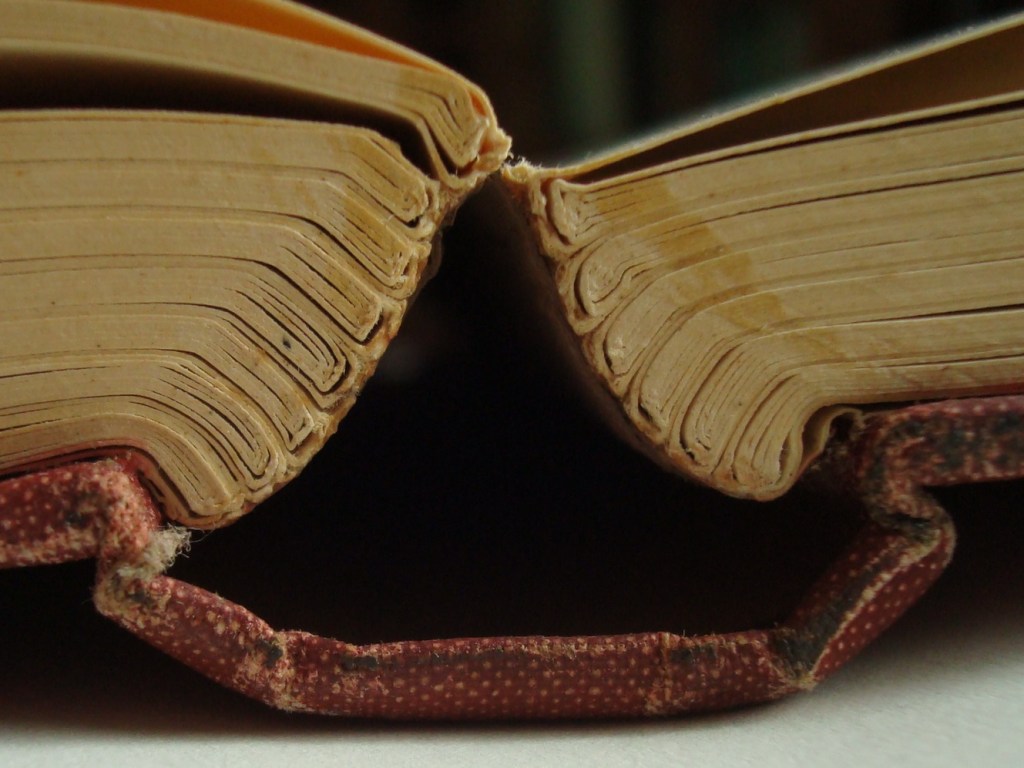

The model that was sewn on tapes contained the highest throw up in the shape of a V when opened to the centre and lying flat (as in Fig. 11). Unpacked sewing on single cords produced a more rounded arch shape due to the stiffer support. Packed sewing on single cords produced an even stiffer support and resulted in a lower arch when opened. The model sewn on double cords had the least amount of throw up because the two cords together were the stiffest. These models show that the stiffer the supports, the less throw up – and the less the paper lies flat. Herbert suggests that the stiffness of the Mohawk paper is also a contributing factor here.

Putting it all together

This research indicates that the uniform structure of packed sewing produces more uniform strain (less deformation) than sewing on unpacked tapes or cords. Reducing localised strain increases the durability of a book spine. Packed sewing gives us control over aspects of sewing that contribute to spine stiffness, a prime factor in a book spine’s longevity and performance. For example, we can use the number and tension of loops between sections to increase or decrease the stiffness of the cords. Combined with the spine lining design suggested in Part I – the goal of which is to also reduce localised deformation at the text block interface and create uniform stiffness – packed sewing on cords is a good choice when optimal durability and opening characteristics are needed.

Of course, raised cords are not suitable for everyone or every book. Could we apply the same techniques to reduce strain when sewing on tapes? Could we, for example, sew packed tapes to reduce a sharp opening radius? Has anyone tried? I would be interested to know. Could we consider the thickness of tapes more carefully as it relates to the neutral axis principle?

There are many ways to achieve overall uniform stiffness in a book spine. It is an interplay between linings, sewing, paper type, size of book, adhesive and more. An understanding of the materials and mechanics discussed in these articles, combined with practical experience, can help us make technically informed decisions, as well as traditional ones.

Bibliography

Conroy, T. (1987) ‘The movement of the book spine’, The Book and Paper Group Annual, 6, pp. 1–22.

Franck, P. (1941) A lost link in the technique of bookbinding and how I found it. Gaylordsville, Connecticut: the author.

Herbert, H. (2012) ‘Sewing models’, Work of the Hand. Available at: https://henryhebert.net/2012/04/19/sewing-models/ (Accessed 12 September 2022).

Ligatus (no date) ‘Throw up (spine features)’, The language of bindings. Available at: https://www.ligatus.org.uk/lob/concept/1666 (Accessed 12 September 2022).

McIlvaine, L. (2017a) Email to Paula Steere, 8 April.

McIlvaine, L. (2017c) Email to Paula Steere, 26 April.

McIlvaine, L. (2017e) Conversation with Paula Steere, 23 May.

McIlvaine, L. (2022a) Conversation with Paula Steere, 21 August.

McIlvaine, L. (2022b) Email to Paula Steere, 9 September.

Miller, J. (2010) Books will speak plain – a handbook for identifying and describing historical bindings. Michigan: Legacy Press.

Paula Steere has an education background and was head of art and design in a secondary school in London before retraining in book and archival conservation at Camberwell College of Arts from 2015 to 2017. She has worked at the College of Arms, the Wellcome Collection, Senate House Library, the London College of Fashion Archive, Victoria and Albert Museum and University College London Special Collections. Currently she is a preventive conservator, volunteer coordinator and grant writer at the Hershey History Centre, an nonprofit museum in Pennsylvania, US. She is also a book conservator in private practice.

Dear Paula, thank you very much for this article and your high-quality research into mechanics of books. It’s a fascinating project, and I hope we’ll be talking about it soon!

Kind regards

LikeLike