The National Archives (TNA) has approximately eight million photographs in its collection, including many formats and types of photographic materials that are housed within files and documents. Photographic prints, roll film, colour slides and glass plate negatives can be found loose in sleeves and envelopes or attached to paper documents and albums with adhesives or metal fasteners. The intermixed storage of these photographic materials with paper documents can pose many preservation and conservation challenges, especially when the photographs are deteriorating or damaged. The deterioration products of cellulose acetate and nitrate negatives can cause irreversible chemical damage to paper. Broken glass plate negatives can mechanically damage fragile paper documents, and people can injure themselves with them. When many broken glass plate negatives were discovered in a file from The National Archives’ collection, the conservators at the Collection Care Department faced many questions and challenges regarding their treatment, storage and access. In this article, I describe the treatment approach we chose and the decision-making process behind it.

Discovering the broken glass plate negatives

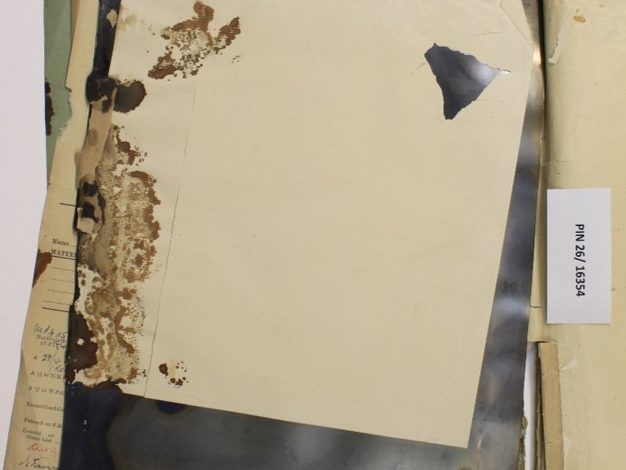

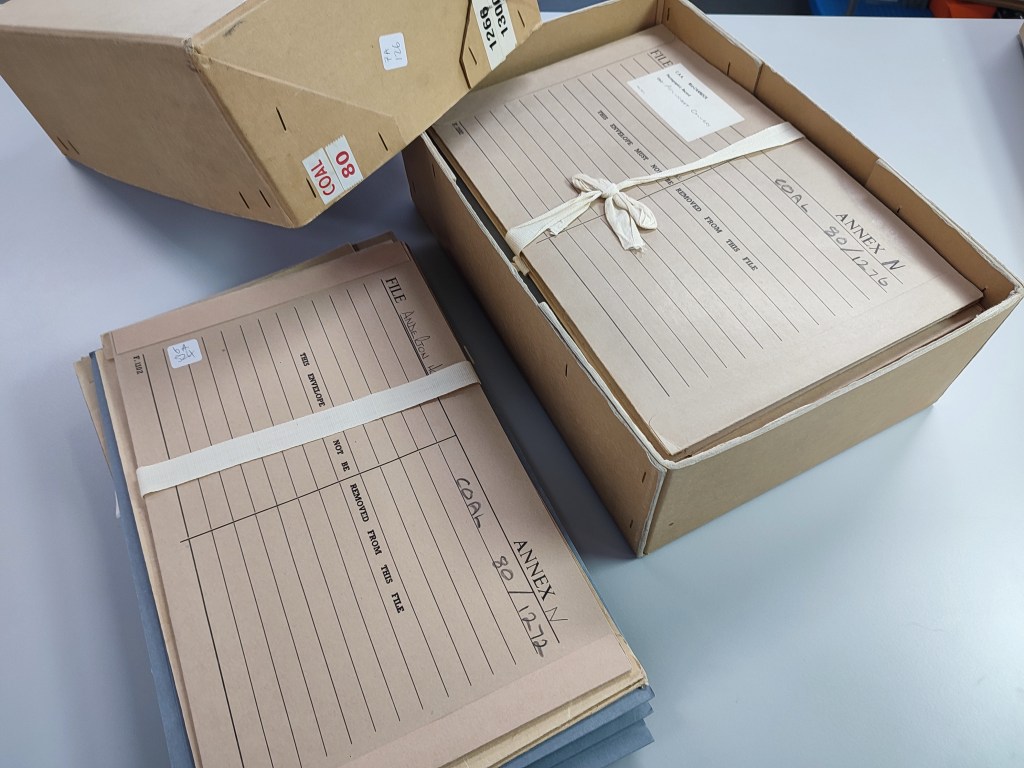

The collection of the National Coal Board at The National Archives consists of files related to various aspects of the British coal mining industry over the period from 1890 to 1990. The series with reference COAL 80 consists of more than 2,050 files that contain photographs and photographic negatives. These files were part of the 2018–2019 survey carried out by the Collection Care department staff and volunteers to locate and identify plastic negatives. In addition to numerous plastic ones, a significant number of glass plate negatives were also discovered. They were housed in glassine envelopes, sometimes with inscriptions and notes, and stored alongside documents in flat folders stacked in boxes. The housing system did not offer sufficient protection for the fragile glass negatives, and as a result, many of them were in poor condition, with extensive breakage. For example, the file COAL 80/1617 contains 31 dry gelatine glass plate negatives (120 × 90 mm), and 25 of them were broken (Figs. 3, 4).

Accessing the file was almost prohibitively difficult: apart from the injury risk from broken glass, careless handling may further damage the negatives themselves, even leading to loss of content. There was a strong case for removing the negatives from the file and storing them separately. However, the extraction of individual items from files can also have many drawbacks: more storage space may be needed, for example, and context may be lost due to separation from the parent documents. Extracting the negatives may seem like a good solution for one single file, but when upscaled to the entire COAL 80 series (2,050 files), it would mean extracting hundreds or even thousands of glass plate negatives – a much more challenging task. When an item is extracted from a file, it receives a new reference number, meaning that the cataloguing team is also involved. Depending on the number of extracted items, this can become a lengthy process. The items also need a new storage location, and free space in the repositories of The National Archives is usually limited and reserved for future accessions. The more items are extracted, the more space they will take up. Therefore, we decided not to extract the glass negatives, but rather to seek an alternative solution that would preserve the integrity of the files and the collection.

Exploring treatment options

Treatments for broken glass plate negatives can be mainly preventive; for example, bespoke housing systems can be built to keep the broken parts together while protecting them from further damage. Such methods include sink mounts made from archival-quality board that keep the individual broken pieces apart, or ‘glass sandwiches’ that seal the pieces between glass sheets, so that the images can be viewed as originally intended. In the case of the broken glass plate negatives from the COAL 80/1617 file, however, these methods would have been very time-consuming and would have provided limited protection because of the large quantity and small size of the broken pieces, and also because many pieces were missing.

We decided instead on a more interventive treatment that would stabilise the damaged glass plates and reduce the need for additional support materials. This would also make it easier to keep the negatives together with the file. Such treatments have already been described in the literature, and they involve adhering the broken pieces together.

To assess the different treatment options and parameters, a series of experiments and tests was carried out on mock-up samples of broken contemporary float glass (2 mm thick), as well as on historical photographs on glass from my personal study collection, which were already broken. The goal was to find the treatment with the optimal speed, adhesion and reversibility. The ideal treatment would keep the repaired negatives stable, reduce the need for additional support materials and allow the negatives to be returned to their original housing, preserving both the context and the ease of access to the files. Ease and speed of application were particularly important so that the treatment could be applied to many more files with broken negatives from the series.

Tailoring the treatment method

The parameters we tested were the positioning and assembly of the broken pieces, the adhesive concentration, the method of adhesive application and the need for additional support materials.

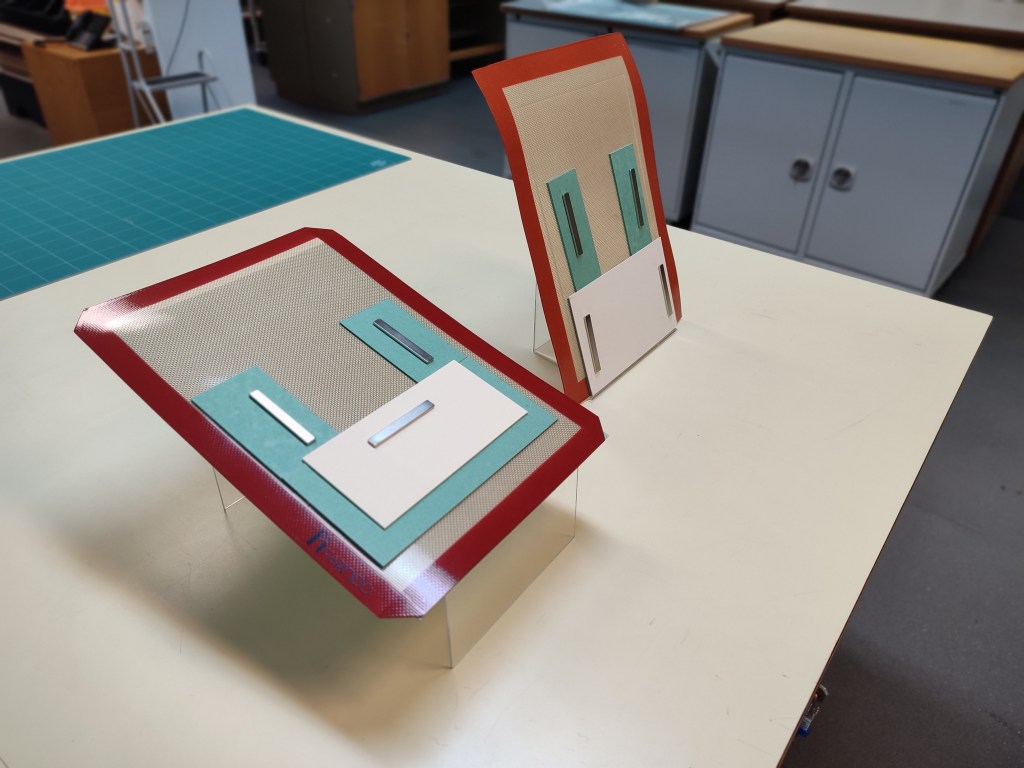

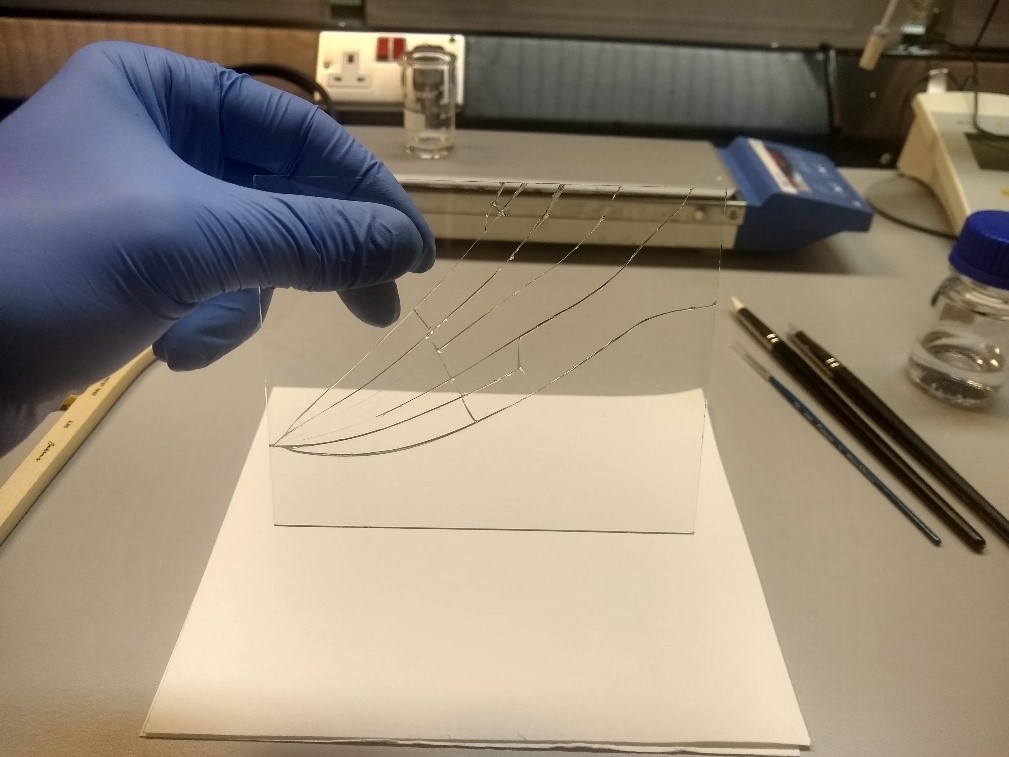

The first step was to assemble all the broken pieces of each negative and to position them correctly. To prevent misalignment and to speed up the process, adhesive must be applied after all the pieces are in place. The angle of the surface on which the pieces are assembled also plays a significant role; for example, if the pieces are assembled on an inclined surface (45–90°), gravity helps align them correctly. The pieces should be placed emulsion side down, so that the adhesive can be applied from the glass side. Capillary action then drives the adhesive through the cracks, and any excess adhesive can be removed from the glass surface after it dries. The adhesive should also not reach the emulsion side, which means that there should be air circulation between the emulsion and the support surface. This would limit the capillary action to the interior of the cracks and would prevent the adhesive from leaking out on the emulsion side. The surface on which the emulsion rests should be non-stick to prevent accidental adhesion. After testing many support materials, we decided on silicone baking mats, as they are non-stick and can be purchased with a textured surface to allow air circulation.

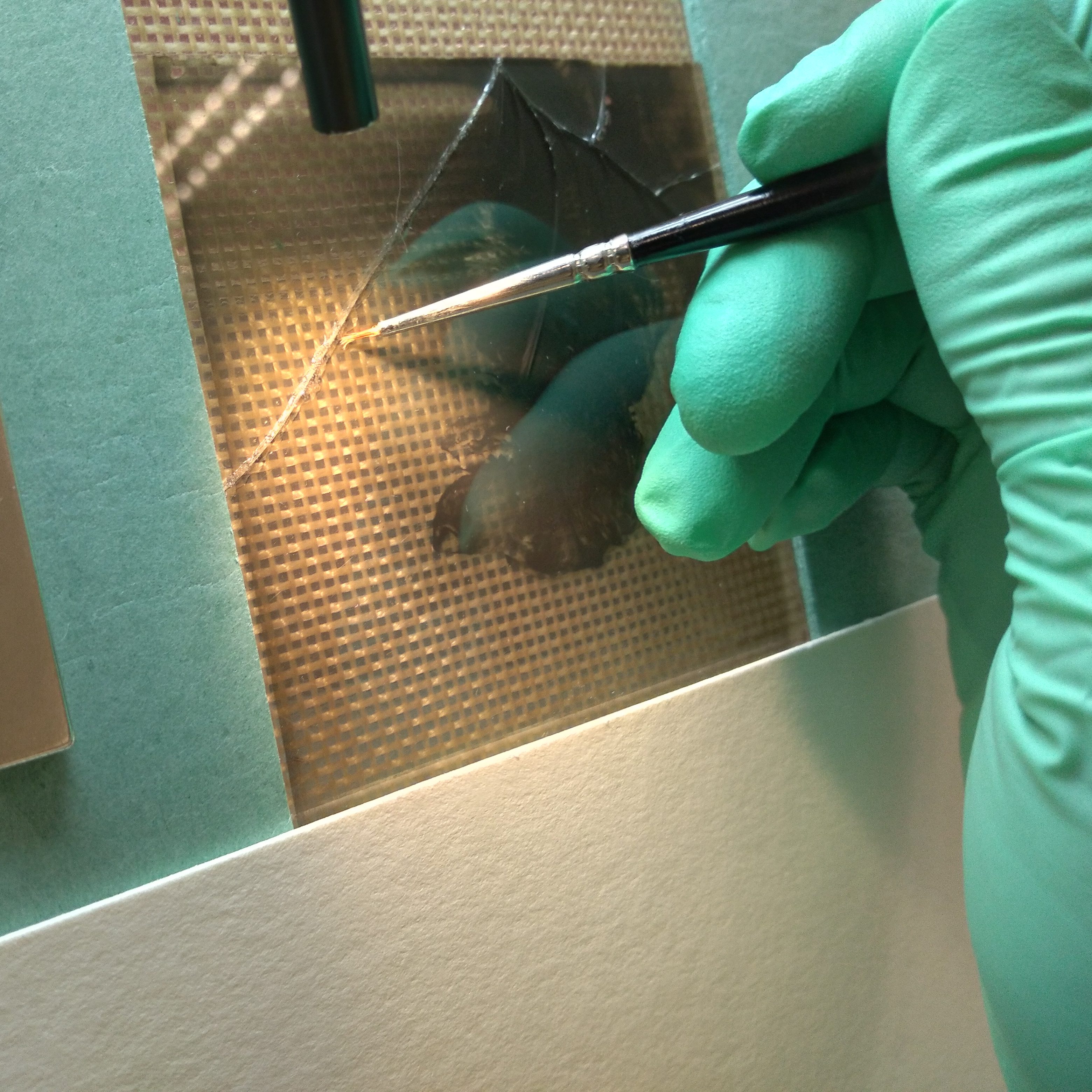

We chose Paraloid B-72 in acetone as the adhesive, as it has been widely used in glass conservation, thanks to its good ageing properties and its refractive index, which is similar to that of glass. The optimal concentration depends on the glass plate size and thickness, the degree of damage and the speed of application. A low concentration means low viscosity, ensuring that the adhesive wicks all the way through the cracks. But a too-low concentration does not provide strong adhesion and could potentially leak on the emulsion side. During the tests, 35% was found to work well with 1- to 2-mm-thick glass without any adhesive leaking onto the emulsion. The negatives we intended to repair were 1.2 mm thick, so they fell within this range. A thin brush was used to apply the adhesive, and the excess was removed after drying for three to five days.

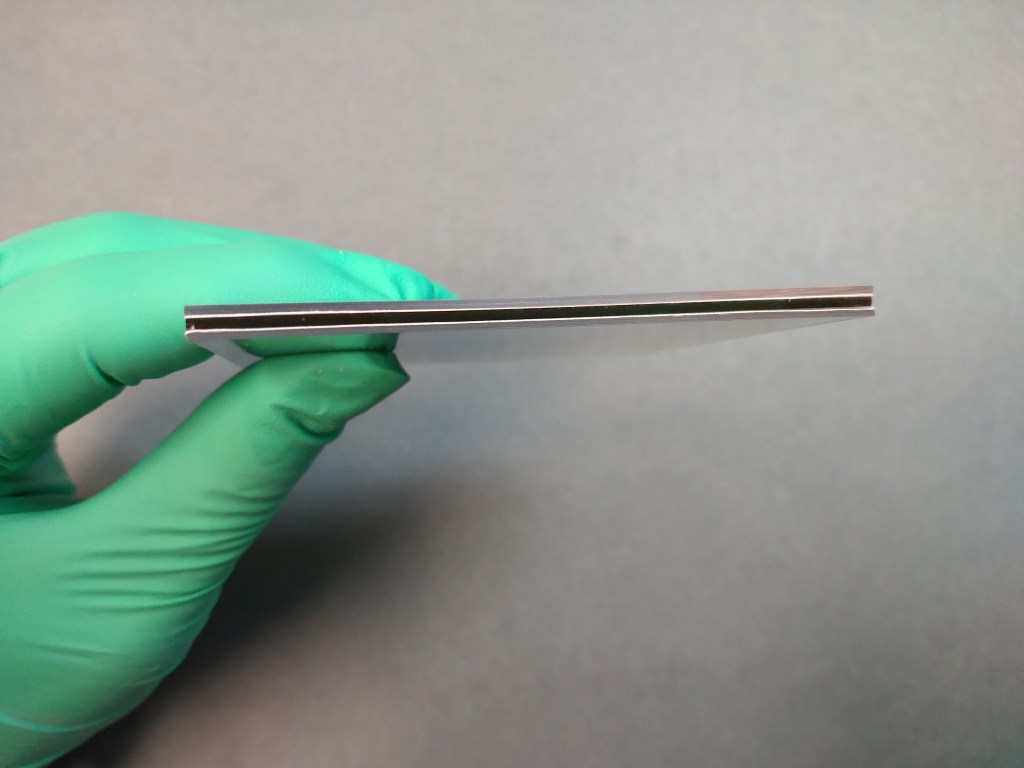

After five days, the repaired glass plates could be lifted and handled safely (Fig. 10). Ideally, the repaired plates would not have needed any additional support; however, our glass plates were broken in many places, so some additional support was still necessary to ensure that they could be handled safely. We used the repaired sample plates to test different support options, including transparent silicone layers, glass, and Vivak®sheets. For silicone, we chose Silicone P-4 supplied by Silicones Inc., mostly because it has passed the Photographic Activity Test. However, the silicone was quickly abandoned because it attracts dust and dirt on its surface. 2-mm-thick glass was also unsatisfactory, as it would have added a lot of thickness and weight to the objects. Thinner glass would have been too fragile.

The last material we tested, Vivak®, is a polyester sheet which can be purchased in a range of thicknesses. It is lightweight, has good optical properties and has passed the Photographic Activity Test; it is also flexible and can be easily cut to the desired shape using a board chopper. Different thicknesses can be used for different levels of damage in the repaired glass plates. A glass plate with one to three cracks can be sandwiched between two sheets of thin Vivak® (0.75 mm), while a more heavily damaged plate might need at least one thicker layer (1 or 1.5 mm) for a more rigid support. Thin Silver Safe paper strips can be positioned along the edges of the Vivak® sheet, secured to the polyester using a small amount of 45% Palaroid B-72 in acetone. These strips act as a separation window, keeping the emulsion from touching the Vivak® surface and preventing the appearance of Newton’s rings (interference patterns). The sandwich can then be sealed using Filmoplast® P90 archival adhesive tape (Figs. 12 and 13).

Evaluation of the treatment on a larger scale

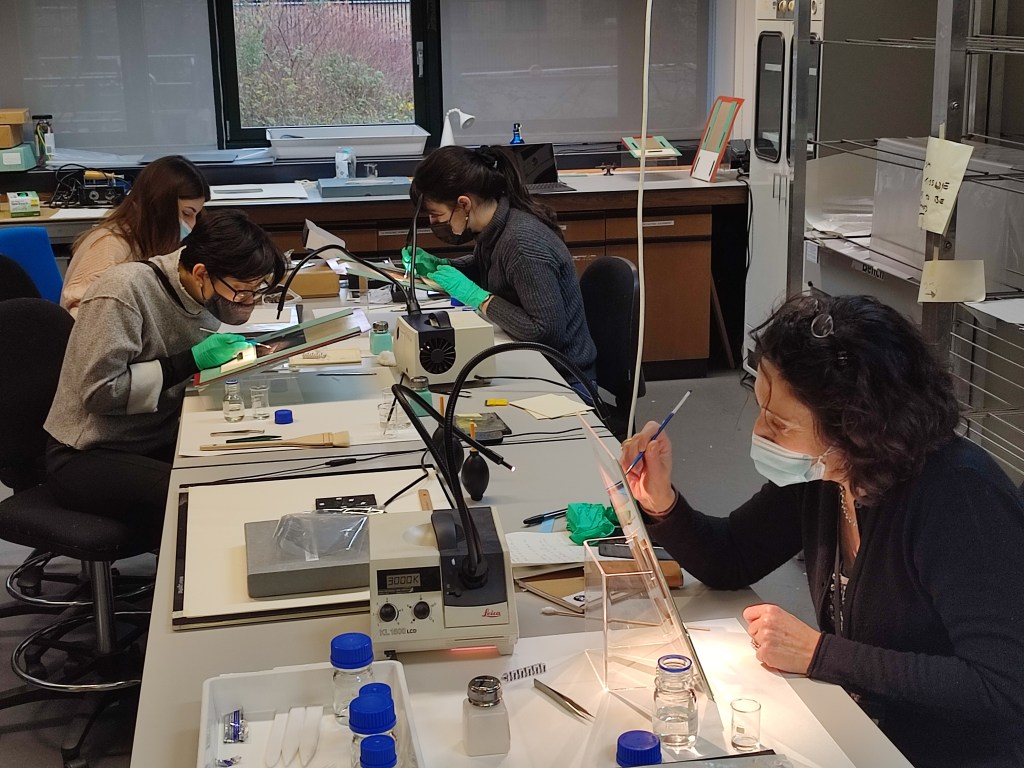

A couple of negatives from the COAL 80/1617 file have already been treated by this method (Fig. 14). The treatment was a success, and the damaged plates can now be handled safely. Before applying the method to the rest of the negatives, we decided to further test its applicability, treatment time and level of difficulty, with the goal of standardising the procedure. More testing would help estimate treatment time more accurately if a larger number of glass plate negatives from the series need to be treated, or if we come across other collections with similar problems. We also hoped to teach the method to interns and other conservation colleagues. Therefore, we organised a mini workshop at The National Archives for the two other conservators from the Collection Care department, as well as for external conservators. Broken glass plate negatives from my study collection were provided for the participants to practise on. The participants had the opportunity to carry out the whole treatment described above: cleaning and preparing the broken plates, consolidating the pieces and adding support materials. The workshop was an excellent opportunity to get feedback on the treatment method and to observe it in practice. The participants said that they greatly enjoyed the hands-on experience, and suggested some improvements. Our overall impression was that the treatment method is simple, effective and reversible, and that it could be adapted to different types of photographs on glass supports in various sizes and conditions (though size and condition can affect treatment time).

Next steps

The positive feedback from the workshop gave us confidence to go ahead with the treatment. There are still details that need to be thought through and fine-tuned; for example, we need to think of a faster way to add the separation Silver Safe paper, as this step can be time-consuming. We would also like to add a barrier material around the edges of the plate to prevent direct contact between the Filmoplast® P90 adhesive tape and the edges of the emulsion. After these concerns are addressed, the method will be used to consolidate the rest of the heavily damaged glass plate negatives from the same file, and the treatment time for different levels of breakage will be monitored. A more detailed survey of the whole series will follow, and the estimates will be applied to other similar files.

Acknowledgements

This project is the result of collaborative work and research that I did together with interns Andra Danila and Martina Paganin. Their constructive input, insightful suggestions and hands-on work were instrumental to the completion of the project. I would also like to thank Barbara Borghese, former senior conservation manager – treatment at TNA, for her relentless support, as well as the workshop participants, Katerina Williams (senior conservator, books and paper, TNA), Beatriz Brandao (conservation intern, TNA) and Stefania Signorello (conservator, Wellcome Collection), for their enthusiasm and feedback.

About the author

Ioannis Vasallos graduated in 2012 from Camberwell College of Arts in London with an MA in Conservation. He had earlier received a bachelor’s degree in Conservation of Antiquities and Works of Art from the University of West Attica in Athens. In 2014, he completed a one-year advanced Icon Photographic Conservation Internship at the National Galleries of Scotland. He has worked as a conservator of photographic materials at the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam and at the National Library of Scotland. In early 2019, he joined The National Archives in London, where he is currently working as a conservator of photographs and paper/archives. Apart from planning and carrying out conservation treatments, Ioannis is managing volunteer projects, and he actively participates in outreach and learning activities in the department. He also has a strong interest in researching historical photographic processes, their deterioration mechanisms and conservation. Currently he is carrying out research in rare pannotypes found in the collection of The National Archives.

Bibliography

Fernanda, V. M., 2005, Photographic Negatives: Nature and Evolution of Processes, 2nd edition, Advance Residency Program in Photograph Conservation, George Eastman House, Image Permanence Institute

Whitman, K., 2007, ‘Case Study: Repair of a Broken Glass Plate Negative’, Topics in Photographic Preservation, Volume 12, pp.175–181

Whitman, K., 2013, ‘Conservation of an American Icon: the Reconstruction of the Lincoln Interpositive’, Topics in Photographic Preservation, Volume 15, pp.14–24

Ronel, N., 2015, ‘Consolidation of Four Flaking Gelatin Glass Plate Negatives from the University of Colorado’. Topics in Photographic Preservation, Volume 16, pp.257–258

Meng Tay, J., 2013, ‘The Glass Plate Negative Project at the Heritage Conservation Centre’, In: Topics in Photographic Preservation, Volume 15, pp.94–106

McCabe, C., 1991, ‘Preservation of 19th-Century Negatives in the National Archives’, Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, Volume 30, No. 1, pp.41–73

Whitman, K., Osterman, M., Chen, J.-J., 2007, The History and Conservation of Glass Supported Photographs. Advanced Residency Program in Photograph Conservation.

Koob, S.P., 2006, Conservation and Care of Glass Objects. Archetype Publications: London.

Suppliers

Vivak® sheets – Amari Plastics: https://amariplastics.com/catalogsearch/result/?q=Vivak

It’s disappointing that the author of this post hasn’t cited the treatment methods that “have already been described in the literature.” Including citations, especially with links, for such article(s) would not only properly credit the work of others but would have been helpful to readers interested in further information about the methods assessed by the author and his students.

LikeLike

Thank you for pointing out that the Book & Paper Gathering had forgotten to include the provided bibliography: this is now corrected. We apologise to the author, Ioannis Vasallos, as well as our readers for this oversight.

LikeLike